1.- CLIL

& CBI : WHEN LANGUAGE AND CONTENT MEET

Language

and Content Meet

In this

paper I will explore how CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) and/or

CBI (Content Based Instruction) could be identified as innovative approaches in

TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) in Argentina. Even

though the CLIL phenomenon and CBI are not new to the TESOL dimension, they

together have become a current topic of discussion and research in the EFL

teaching practices in Argentinian education.

With the

purpose of building a sound theoretical framework, I will first describe CLIL and

attempt to establish a connection with CBI, focusing on theoretical

underpinnings and multiples standpoints found in the literature. Secondly, I

will discuss whether such an innovation is more theory-driven, classroom

practices-driven, or a bridge constructed with contributions from both fronts.

Following

the theoretical discussion I will present examples of this innovation in my context

of professional practice and development.

One of the

first issues to explore is to determine whether CLIL and CBI are the same phenomenon

or whether the latter could be interpreted as a realisation of the former.

The term CLIL was first introduced in 1994 by David Marsh, who expanded its implications

in 1996 after Finland became a new state member of the European Union (EU)

(Lucietto, 2008:29). Marsh’s concept was most welcomed by the EU as one of their

crucial aims is to develop the plurilingual competence in their citizens.

Marsh (

On the

other hand, Dalton-Puffer (2007) restricts the scope of CLIL to educational settings

and classrooms where the environment provides opportunities for acquiring learning

as opposed to explicit practices. Her definition for the term under

consideration is [CLIL] refers to educational settings where other than the

students’ mother tongue is used as a medium of instruction. (2007: 1).

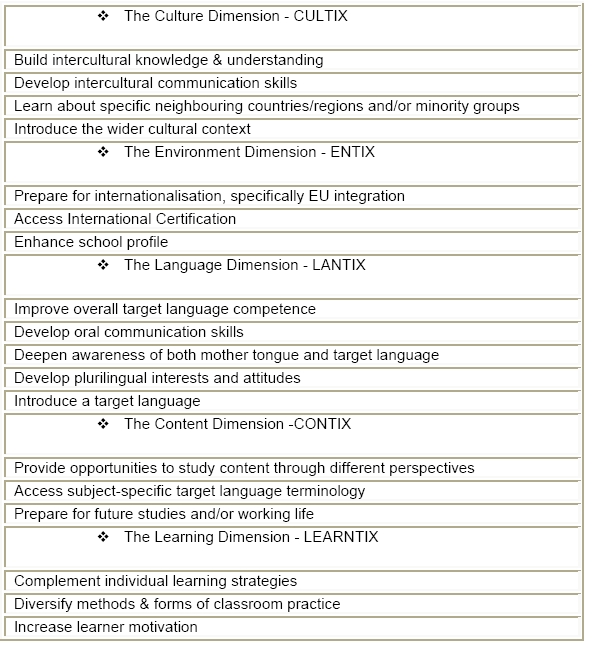

The CLIL

Project, far from being a mere definition (Lucietto, 2008:37), also offers a number

of dimensions which have been embraced by countries outside the EU (Bebenroth

and Redfield, 2004).

The Annual

Conference for Teachers of English organised by FAAPI (Federación Argentina de

Asociaciones de Profesores de Inglés) proposed the topic “Using the Language to

Learn – Learning to Use the Language” as the core issue of the 2008 event. Such

subject matter is closely connected to the realms of CLIL. The regional

association, APISE, which was in charge of organising this conference present

the CLIL dimensions1 (Table 1):

Table 1:

CLIL dimensions. Source: APISE, 2008

1 Also

available at http://www.clilcompendium.com/clilcompendium.htm. Last accessed

However,

it is in Europe where CLIL has been widely recognised as a tool to achieve the

plurilingual conscience the EU has established as a crucial aim among its state

members (Salatin, 2008:11-12). In her book on CLIL classrooms, Dalton-Puffer

(2007) gives a detailed account of how this approach has been applied at a

university level in Austria and the discourse features, academic language

functions and learning environment it produces. According to Dalton-Puffer and

Nikula (2006), Austria is not the only country where CLIL has been adopted.

They claim it has become a common practice in many European countries such as

Finland. In this context, needless to say, the rationale lies in the conviction

that learners, regardless of the CLIL settings, will develop their

communicative competence if they use the target language as a medium

for

learning since they will engage in building different communicative events and social

practices by working collaboratively and with a goal that goes beyond the

explicit linguistic knowledge. Another country is to consider is Italy, where

CLIL projects or models (Lucietto, 2008) not only use English, but also German

as a medium of instructions in subjects such as

Mathematics

and Geography (Fantin et al. 2008: 1731-83; Ambrosi et al. 2008:

191-264). In the literature review, Dalton-Puffer (2007:1) asserts that even

though there are many terms, which carry different implications, in use, such

as CBI, Bilingual Teaching, and English Across the Curriculum among others, the

term CLIL is now established in the academic and educational spheres. However,

Navés (2000) simply states that while CLIL is a term used in Europe, CBI is the

preferred choice in the USA and Canada, this latter being generally recognised

as the country where this trend originated in the 1960’s. We will see, however,

that this distinction is far from being clear-cut.

It is

worth noticing that the definitions advanced so far share the concept of

subject, content or instruction. If we bear in mind the Content Dimension

(Table 1) and its foci we can clearly see how CBI fits into such a dimension.

Therefore, we might say that Content-Based Instruction, also called

Content-Based Learning (Wolff, 1999:178-180),might be viewed as a branch

(Wolff, 2002:214) that has developed and evolved in its own right with

different underpinning principles. Brinton et al. (2003: 265) define CBI

as

teaching that integrates particular content with language-teaching aims,

with a goal to

develop use-oriented second or foreign language skills; concurrent

teaching of

academic subject matter and second language skills, following a sequence

determined

by a particular subject matter with a content-driven curriculum.

We clearly

see that, even though the main goal is foreign or second language acquisition,

the emphasis is not on learning the language (Davies, 2003) but acquiring content

in a context where language becomes a psychological tool, one which mediates

between the learners and the subject matter. This mediation and integration should

be a dual commitment (Stoller, 2002) made by teachers who truly believe that CBI

can offer a better environment for language acquisition. Consequently, it is expected

that learners when fully immersed in this cycle will benefit from both language

and content, since as they improve their L2 competence, they will be able to

learn more content, and, in turn, by acquiring more content knowledge they will

master the target language used as medium of instruction (Stoller, 2002). Not

only content knowledge

will

affect their performance in the L2 but it will also transfer to their mother

tongue as

they might

integrate new concepts in the traditional curriculum.

This

concern in content-based language teaching and learning is not recent; it is

rooted in the 1960’s when a French immersion project was implemented in Canada

in postsecondary education. This alternative model spread in the USA and developed

in another model termed LSP (Language for Specific Purposes) which aimed at

preparing learners for university level and the working domain (Brinton et

al. 2003:5-9; Swain and Johnson, 1997:1; Troncale, n/d:2). All these

programmes proved to be effective in achieving content and L2 literacy outcomes

in adults (Sticht, n/d).

In general

terms, CBI or CBL adherents (Woff, 1999:178-180) believe that this approach can

develop a higher competence in the foreign language since learners are exposed

to longer periods of input, when it is sustained in time (Murphy and Stoller, 2001:3-4),

and they are engaged in real meaningful interaction as the process is supported

by authentic materials which, together with an innovative instruction, will help

them develop strategies such as hypothesis building and testing. Eventually, learners

will gain subject and world knowledge which will enable them to interact in the

real world (Woff, 1999:180).

With the

purpose of establishing some founding principles in context, Brinton et al. (2003:1-4)

propose five different rationales. First, learners’ needs and potential uses of

the target language must be taken into account. Second, such needs should be

met by the use of relevant content as to promote subject and language development.

Third, this approach works best if it anchored in learners’ previous knowledge

of both subject matter and language. Fourth, the focus should be on the

macroaspects of language, that is, on discourse organisation rather than on the

sentence level. Last, even though it has been suggested that one of the

features of CBI is the use of authentic material, the input in the target

language should be understood by learners and offer the possibility to continue

improving their linguistic knowledge.

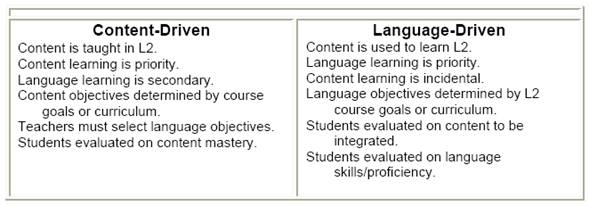

From its

incipient implementation to current trends, CBI has evolved in many different directions

and it might be better comprehended if we see it as a continuum (Shang, 2006;

Hernández Herrero, 2005; Brinton et al. 2003; Met, 1999) where language

is at one end and content at the other.

Met (1999) offers a clear continuum of

language-content integration (Table 2)

Table 2: Continuum of language-content

integration. Source: Met (1999)

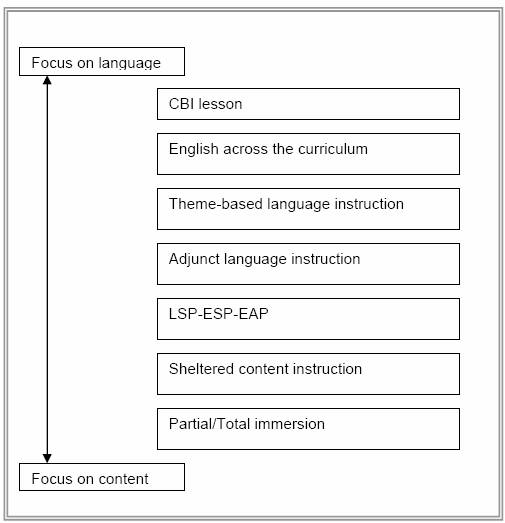

It goes without saying that within this

continuum, varied models are found. Therefore,

I

propose the following CBI continuum (Table 3).

Table 3: CBI continuum

Beginning at the language extreme, CBI lesson

is a reduced perspective suggested by Peachey (2003). CBI is equated to a

lesson where its topic responds to learners’ interests ranging from their pop

starts to scientific issues. One of its features is that though it focuses on

content and collaborative work, it is not sustained in time. It is seen rather

as a lesson within the EFL syllabus.

Whitney (2002) proposes in his book Dream Team

3, textbook adopted by a large number of secondary schools in Argentina, a

section called English Across the Curriculum in each unit of the book. This

reading section is characterised by language within the range of learners’

grammatical competence though it presents new lexical items in a set related to

any subject. In my opinion it is close to the language extreme since it is

neither content-related to the school curriculum nor coherent as regards context.

Theme-based instruction occurs within the

ESL/EFL or any other target language course and though the context is given by

specific content areas, the focus of evaluation lies on language skills and

functions. A theme-based course will be structured around unrelated topics

which will provide the context for language instruction (Brinton et al. 2003:

14-15).

At the centre of the continuum, the adjunct

model (Met, 1999) combines a language course with a content course. Both

courses share the same content base and the aim is to help learners at university

level (Kamhi-Stein, 1997; Iancu, 1997) master academic content, materials, as

well as language skills.

The Language for Specific Purposes models, on the other hand, are aimed at preparing

learners to meet the demands coming from academic instruction as well as job

requirements. Although the focus is on content, materials can be structured

around microskills, functions and specific vocabulary (Brinton et al. 2003: 7).

Next in the continuum, the sheltered-content approach consists of a content

course taught by a content area specialist in the target language. The student

population consists of non-native speakers who are expected to master authentic

material and, most of all, the content course syllabus (Brinton et al. 2003:

15-22).

Last, total immersion programmes can be mainly

found in Canada and the USA at elementary and secondary levels. It has been

applied to second language acquisition, in settings where language is learnt

incidentally through content instruction and interaction within the classroom

context (Dalton-Puffer, 2007; Brinton et al. 2003; Grabe and Stoller, 1997:80).

Regardless of their location in the CBI

continuum, all these models share the view that language knowledge is best

acquired when situated in a context where content knowledge provides the basis

of instruction. However, it should be pointed out that the varied perspectives

described above seem to work best when learners already have some knowledge of

the target language.

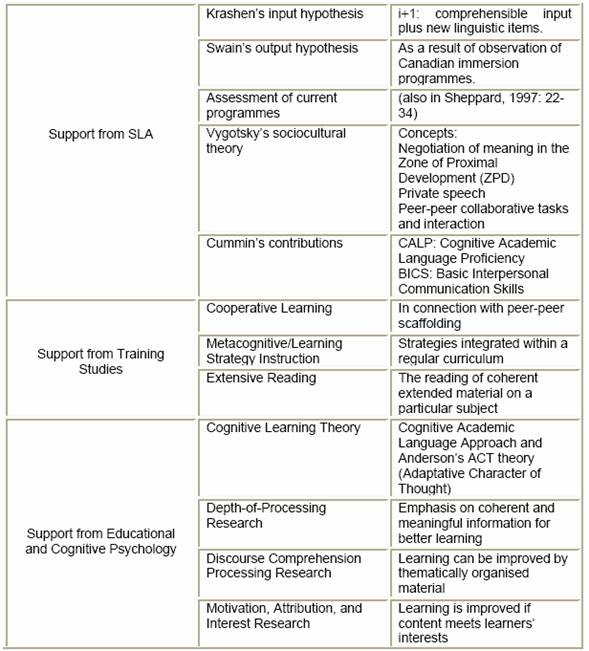

These models are the product of both theory and classroom practice. Grabe and

Stoller (1997:5-21)2 provide a description of CBI research foundations. Their

contributions,which present evidence of the interplay between theory and

practice, could be summarised as follows (Table 4):

Table 4: Support for CBI: theory and

classroom-driven

The adoption of a content-based approach in my

professional practice began at a bilingual school in 2004 when my students

expressed the need to English as a medium of instruction. Consequently, I

proposed a syllabus to teach Literature using unabridged texts together with

authentic material about literary studies. The change improved my students’

communicative competence, particularly their vocabulary knowledge and their reading

skills.

A year later I designed a new course for my

upper-intermediate students who were in their last year of secondary education.

Once a week during a whole academic year, they were taught Critical Thinking

together with Literature.

In 2006, it was decided that different versions of CBI should be extended to

all EFL Courses in primary and secondary levels. At present, as regards primary

education, learners have, besides following a traditional EFL course, Computers

Studies and Science taught in English.

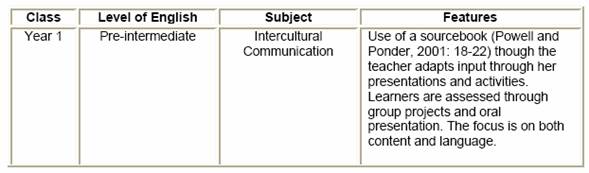

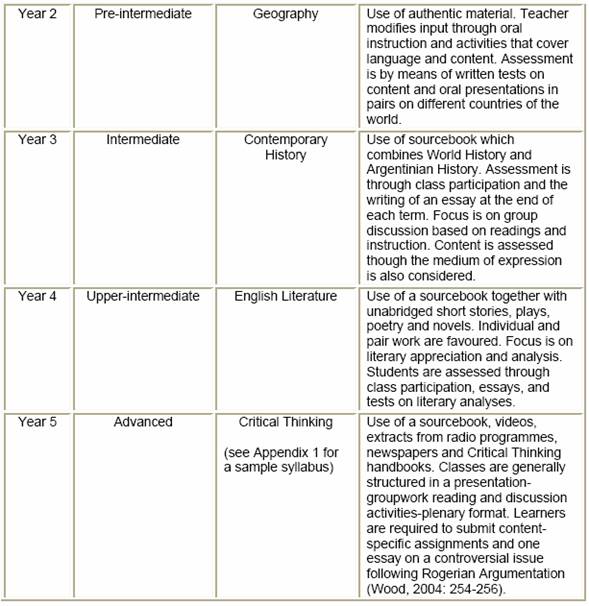

As for the secondary level, learners follow a traditional course with textbooks

which might be oriented to language skills and international exams such as FCE

(First Certificate in English) and CAE (Certificate in Advanced English). In

order to introduce CBI, we designed a programme (table 5) taking into account

learners’ level of English and curriculum content knowledge in Spanish. The

proposed subjects are taught in English by their English teachers once a week.

Table 5: CBI courses at Fundación Educativa

Esquel Bilingual School

In

I have also designed and taught some

theme-based lessons at the last year of secondary school at San Luis Gonzaga

School. At this school, English as a subject in the school curriculum is only a

two-hour class per week; however most of the students in the highest years

attend English private lessons.

Since 2006, English has become involved in the

subject Research Project which is taught in Year 5. Students are expected to

carry out research on a particular area within Chemistry, Biology, or Physics,

and produce at the end of the process a research paper for the community.

Though students write their papers in Spanish, abstracts are written in English

to familiarise them with scientific conventions.

Therefore, their first lesson (see Appendix 2)

in English is about Knowledge-Science-Education, and, by the beginning of the

second term, they have a lesson about Research Methodology, mainly focused on

how to organise their research papers and how to write an abstract. Students

have expressed that they can use English for real purposes and that it is a way

of acquiring specific vocabulary which they might need in university courses.

First, we

discovered the basis of CLIL and how it is realised into several dimensions where

content and second or foreign language acquisition in classroom settings interact

with one another with the purpose of providing learners with an improved context

for language learning. One of CLIL dimensions invited us to identify CBI as an innovation

in TESOL which is rooted both in theory and classroom practices. Accounts of

how CBI approaches can be implemented suggest that there is a whole continuum of

models teachers can adopt; from strong versions where content is cornerstone to

a weak version where content provides the context for language instruction.

Such assertions have been exemplified by national conferences, research and current

projects set in classrooms where learners have an intermediate command of

English.

In

conclusion, it might be said that CBI is an approach which can illuminate our

EFL curricula; however it is vital that teachers should be trained so as to

help them explore the horizons this innovation has to offer.

REFERENCES

Ambrosi, S., L. Amort, F. Brigadoi, A. Giorio,

and A. Zorzi (2008) ‘CLIL all’Istituto

comprensivo di Pedrazzo,’ in Lucietto, S.

(ed.)…e allora…CLIL! .Trento: Editore Provincia

Autonoma di Trento-IPRASE del Trentino.

APISE (2008) Content and Language

Integrated Learning. At

http://www.apise.org.ar/what_is_clil.htm (Date

accessed 26th October, 2008).

Banegas, D. (2008) ‘The Relevance of

Content-Based Instruction,’ in Lòpez Barrio, M. (ed.)

Using the Language to Learn - Learning to Use

the Language XXXIII FAAPI Conference

Proceedings. Santiago

del Estero: APISE.

Bebenroth, R. and M. Redfield (2004) ‘Do OUE

Students Want Content-Based Instruction?

An Experimental Study.’ Osaka Keidai Ronshu

55:4 at

www.bebenroth.eu/Downloads/CententBasedInstrucRube55.04DaiKeiDai.pdf

(Date

accessed 25th October, 2008).

Brinton, D., M. Snow, and M. Wesche (2003)

(2nd edition) Content-Based Second

Language Instruction. Ann

Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007) Discourse in

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)

Classrooms. Philadelphia:

John Benjamins.

Dalton-Puffer, C. and T. Nikula (2006)

‘Pragmatics of Content-based Instruction: Teacher

and Student Directives in Finnish and Austrian

Classrooms’. Applied Linguistics 27/2: 241–

267.

Davies, S. (2003) Content Based Instruction

in EFL Contexts. At

http://www.iteslj.org/Articles/Davies-CBI.html

(Date accessed 21st October, 2008).

Fantin, F., E. Fratton, and W. Paoli (2008)

‘CLIL all’Istituto comprensivo Centro Valsugana,’

in Lucietto, S. (ed.)…e allora…CLIL! .Trento:

Editore Provincia Autonoma di Trento-

IPRASE del Trentino.

Grabe, W., and F. Stoller (1997) ‘A Six-T’s

Approach to Content-Based Instruction’, in

Snow, M. and D. Brinton (eds.) The

Content-Based Classroom. White Plains: Longman.

Grabe, W., and F. Stoller (1997)

‘Content-Based Instruction: Research Foundations,’ in

Snow, M. and D. Brinton (eds.) The

Content-Based Classroom. White Plains: Longman.

Hernández Herrero, A. (2005) ‘Content-based

instruction in an English oral communication

course at the University of Costa Rica.’ At

http://revista.inie.ucr.ac.cr/articulos/2-

2005/archivos/oral.pdf (Date accessed 23th

October, 2008).

Iancu, M. (1997) ‘Adapting the Adjunct Model:

A Case Study,’ in Snow, M. and D. Brinton

(eds.) The Content-Based Classroom. White

Plains: Longman.

Khami-Stein, L. (1997) ‘Enhancing Student

Performance through Discipline-Based

Summarization-Strategy Instruction,’ in Snow,

M. and D. Brinton (eds.) The Content-Based

Classroom. White

Plains: Longman.

Lucietto, S. (2008) ‘CLIL, un’innovazione tutta europea’, in Lucietto,

S. (ed.)…e

allora…CLIL! .Trento:

Editore Provincia Autonoma di Trento-IPRASE del Trentino.

Met. M. (1999). Content-based instruction:

Defining terms, making decisions. NFLC

Reports. Washington, DC: The National Foreign

Language Center. At

http://www.carla.umn.edu/cobaltt/modules/principles/decisions.html

(Date accessed 24th

October, 2008)

Murphy, J. and F. Stoller (eds.) (2001)

‘Sustained-Content Language Teaching. An

Emerging Definition.’ TESOL Journal

10/2-3:3-4.

Navès, T. (2000) Grid of CBI and CLIL. At

www.ub.es/filoan/CLIL/CLILbyNaves.htm (Date

accessed 27th October, 2008)

Peachey, N. (2003) Content based

instruction. At

http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/think/articles/content-based-instruction

(Date accessed

22th October, 2008).

Powell, P. and R. Ponder (2001) ‘Sourcebooks

in a Sustained-Content Curriculum.’ TESOL

Journal 10/2-3:18-22.

Salatin, A. (2008) ‘Presentazione,’ in

Lucietto, S. (ed.) …e allora…CLIL! .Trento:

Editore

Provincia Autonoma di Trento-IPRASE del

Trentino.

Shang, H. (2006) ‘Content-based Instruction in

the EFL Literature Curriculum’. The Internet

TESL Journal, XII: 11,

at http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Shang-CBI.html (Date accessed 20th

October, 2008).

Sticht, T. (nd) The Theory Behind

Content-Based Instruction. At

http://www.ncsall.net/?id=433 (Date accessed

20th October, 2008).

Stoller, F. (2002). Content-Based

Instruction: A Shell for Language Teaching or a

Framework for Strategic Language and Content

Learning? At

http://www.carla.umn.edu/cobaltt/modules/strategies/Stoller2002/READING1/stoller2002.ht

m (Date accessed 24th October, 2008).

Swain, M. and Johnson, R. (1997) ‘Immersion

education: A category within bilingual

education’, in Johnson, R., and M. Swain

(eds.) Immersion Education: International

Perspectives.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Troncale, N. (nd) Content-Based

Instruction, Cooperative Learning, and CALP Instruction:

Addressing the Whole Education of 7-12 ESL

Students. At http://journals.tclibrary.

org/index.php/tesol/article/viewFile/19/24

(Date accessed 22th October, 2008).

Whitney, N. (2002) Dream Team 3. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Wolff, D. (1999) ‘Languages across the

curriculum: A way to promote multilingualism in

Europe,’ in Gnutzmann, C. (ed.) Teaching

and Learning English as a Global Language.

Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag.

Wolff, D. (2002) ‘Content and language

integrated learning: a framework for the

development of learner autonomy,’ in Little,

D., Ridley, J. and Ushioda, E. (eds.) Learner

Autonomy in the Foreign Language Classroom:

Teacher, Learner, Curriculum and

Assessment. Dublin:

Authentik.

Wood, N. (2004) Perspectives on Argument. Upper

Saddle River: Pearson.

APPENDIX 1: Critical Thinking, sample syllabus

CRITICAL THINKING

SYLLABUS with BIBLIOGRAPHY 2007 (students will

have underlined material)

Set One

1- What is Critical Thinking? (Fisher, 2004:

1-14).

2- A perspective on argument (Wood, 2004:

3-20).

3- Argument style (Wood, 2004: 41, 47, 49-61).

4- The structure of an argument (Diestler,

1998: 3-11, 12-13).

5- Considering some issues 1 (Numrich, 1995)

- Give me my place to smoke.

- Gang violence

- Facing the wrong end of a pistol

Set Two

1- Logic at a glance.

2- The language of reasoning (Fisher, 2004:

15-32)

3- Assumptions (Diestler, 1998: 78-80; 47-50)

4- Deductive reasoning (Diestler, 1998:

80-100)

5- Inductive reasoning (Diestler, 1998:

101-222)

6- Considering some issues 2 (Numrich, 1995)

- Is it a sculpture, or is it food?

- Women caught in the middle of two

generations.

- What constitutes a family?

Set Three

1- The Toulmin Model: the essential parts of

an argument (Wood, 2004: 126-145;

146-151).

2- Types of claims (Wood, 2004: 159-196;

Fisher, 2004: 82-105).

3- Types of proof (Wood, 2004: 199-218, 220).

4- Fallacies (Wood, 2004: 231-237; Diestler

1998: 224-261).

5- Considering some issues 3 (Numrich, 1995)

- Green consumerism.

- Finding discrimination where one would hope

to find relief.

Set Four

1- Rogerian argument and common ground (Wood,

2004: 251-259).

2- Visual and oral argumentation (Wood, 2004:

394-411).

3- The power of language and the language of

power (Diestler, 1998: 264-307).

4- Suggestion in media (Diestler, 1998: 310-340; 341-353).

5- Writing a research paper that presents an

argument (Wood, 2004: 294-382).

APPENDIX 2: A lesson on

Knowledge-Science-Education, March 2008 (what follows is a sketch of what was

done in class)

1. Remind stu of booklet for this year

2. Introduce topic. Elicit answers by asking

What is knowledge? How has knowledge been

divided and put in black and white?,

brainstorm ideas, invite stu to write on the board.

3. Ask students to work in groups of three.

Answer these questions:

1- We generally divide sciences into two broad

groups. Which are they?

2- Give five examples of each category.

3- What are the features of each group? What

makes them distinctive?

4- Why do some people say that Natural

Sciences are more scientific and

factual even truer than Social Sciences?

5- What’s the difference between rationalism

and empiricism?

6- How do we imagine a typical scientist?

Personality? Appearance?

7- Why is it said that science and feelings

are incompatible?

8- What’s the role of education as regards

Science?

9- How can you ‘murder’ innocence in young

learners?

10- How important is imagination for you? And

for scientists?

11- Are you more logical that imaginative or

the opposite?

4. Plenary: compare answers and make general

comments.

5. Pairwork: listen to the song GOODBYE MR. A,

and edit the lyrics (handout). There are ten

wrong words. Then compare answers with another

group.

6. All together: listen again and correct. How

can you relate this song to today’s topic?

Goodbye Mr A (The Hoosiers, 2007) EDITED

VERSION

There’s a hole in your logic

You who know all the answers

You claim science ain’t magic

And expect me to buy it

Goodbye Mr A

You promised that you would love us

But you knew too much

Goodbye Mr A

You had all the answers but no human touch

If life is subtraction your number is up

Your love is a fraction it’s not adding up

So busy showing me where I’m wrong

You forgot to switch your feelings on

So so superior are you not?

You’d love a little bit but you forgot

(repeat chorus)

Goodbye Mr A

The world was full of wonder

Til you opened my eyes

Goodbye Mr A

Wish you hadn’t blown my mind

And killed the surprise

(repeat chorus)

© 2011 by Dario Banegas.

------------------------------------------------------------------------