SHARE

An

Electronic Magazine by Omar Villarreal, Marina Kirac and Martin Villarreal ©

Year 9

Number 189 July

31st 2008

12,759 SHARERS are reading this issue of SHARE this week

__________________________________________________________

Thousands of candles can be lighted from a single candle, and the life of the

candle will not be shortened. Happiness never decreases by being SHARED

__________________________________________________________

Dear SHARERS,

Some of you might have already come back from your

winter holidays ready to start the new semester filled with renewed energy and illusions.

And as, we must all sadly acknowledge, today we need an extra dose of energy to

cope with the hard reality of Argentinian classrooms.

Teaching has never been an easy task, but of late it has become more of a high-risk profession than anything else, and the worst part of it is that the classroom teacher is often rendered defenseless in the face of aggression from his own pupils and their families. No matter how hard some school heads try to preserve their best “human resources”, there is always somebody higher up on the educational pyramid who will be willing to lend a “friendly” (or should I say “demagogic”) ear to the (often unjustified or whimsical) complaints of parents who feel, just to mention a few well-worn examples, that their children deserve to be promoted to the next grade because “they have made a great effort” or are being ill-treated by their teachers because they give them too

much homework and interfere with their right to leisure or because their

teachers are outright “authoritarian” because they demand a minimum of respect

and attention from those that they are supposed to help those very parents to educate.

The silver alliance between school and society appears to have broken and we

can only dread at the consequences of such a divorce. We believe it is high

time the educational authorities stopped (at least for some time!) tinkering

with cosmetic educational and curricular reforms and devoted more of their time

to promote an honest debate between all parties concerned and helped us find new

and creative ways to restore to schools and teachers the due respect we once

enjoyed and that has now been replaced by more “progressive” forms of cohabitation that we can hardly define

as “collaboration”. Part of the responsibility for such a change is and will

always be in our hands.

Love

Omar and Marina

______________________________________________________________________

In SHARE 189

1.- The Liberating Potential of Grammar in English

Language Teaching

2.- Using the

Socratic Method to teach Culture in EFL Classrooms

3.- Ten Helpful Ideas for Teaching English to Young

Learners

4.- Advanced

Vocabulary in Context: Jeans & Co.

5.- XL Jornadas de Estudios Americanos

6.- II Jornadas del Norte Argentino: Estudios

Literarios y Lingüísticos

7.- News from The British Council

8.- I Congreso Latinoamericano Bilingüe de

Programación Neurolingüística

en Educación

9.- Taller de Traducción de Textos Médicos

10.- Seminar on Teaching English through Content

11.- The

12.- On Target: Business English For Teachers

13.- Net Learning Courses for the Second Semester

14.- Workshops in celebration of ARICANA’S 65th

Anniversary

15.- Nuevo

Blog Colaborativo

16.- A

Message from “On the Road”

17.- Cuartas Jornadas sobre Didáctica de

18.- FLACSO

Workshop with Dr. Joseph Tobin

19.- Talleres de Capacitación de “Language

Unlimited”

20.- Curso sobre la metodología del WebQuest

21.- Cursos de Posgrado en

22.-

“The Mystery of the Grey

Man” by Fancy Fun Group

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]()

1.- THE

LIBERATING POTENTIAL OF GRAMMAR IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING

Teaching grammar as a

liberating force

By Richard Cullen

The idea of grammar as a ‘liberating force’ comes from a paper by Henry

Widdowson (1990) in which grammar is depicted as a resource which liberates the

language user from an over-dependency on lexis and context for the expression of

meaning. In this paper, I consider the implications for second language teaching of

the notion of grammar as a liberating force, and identify three key design features

which, I propose, need to be present in any grammar production task in which this

notion is given prominence. These are: learner choice over which grammatical

structures to use; a process of ‘grammaticization’ where the learners apply

grammar to lexis; and opportunities to make comparisons and notice gaps in their

use of grammar. I then discuss, with practical examples, types of grammar task

which exhibit these features. These tasks all derive from traditional ELT practice,

but have been revitalized to support an approach to teaching grammar which

emphasizes its liberating potential.

The liberating

potential of grammar

In an essay entitled ‘Grammar, and nonsense, and learning’,Widdowson

(1990: 86) wrote:

. . . grammar is not a constraining imposition but a liberating force: it

frees us froma dependency on context and a purely lexical categorization

of reality.

Given that many learners—and teachers—tend to view grammar as a set of

restrictions onwhat is allowed and disallowed in language use—‘a linguistic

straitjacket’ in Larsen-Freeman’s words (2002: 103)—the conception of

grammar as something that liberates rather than represses is one that is

worth investigating further. In this paper, I first explore the implications of

this statement for our understanding of the nature of grammar and the role

it plays in communication, and then go on to discuss how this

understanding might inform approaches to teaching grammar in second

language classrooms.

Widdowson’s conception of grammar as a liberating force may be a striking

image, but what he meant by it is not contentious. Without any grammar,

the learner is forced to rely exclusively on lexis and the immediate context,

combined with gestures, intonation and other prosodic and non-verbal

features, to communicate his/her intended meanings. For example, the

three lexical items ‘dog eat meat’ could be strung together in that order to

communicate the intendedmessage that ‘the dog has eaten themeat (which

we were going to cook for dinner)’, provided there is enough shared context

between the interlocutors—the empty plate, the shared knowledge of the

dog, the meat and our plans for dinner—to allow the utterance to be

interpreted correctly. With insufficient contextual information, the

utterance is potentially ambiguous and could convey a range of alternative

meanings, such as:

1 The dog is eating the meat.

3 Dogs eat meat.

It is grammar that allows us to make these finer distinctions in

meaning—in the above examples, through the use of the article system,

number, tense, and aspect. It thereby frees us from a dependency on lexis

and contextual clues in the twin tasks of interpreting and expressing

meanings, and generally enables us to communicate with a degree of

precision not available to the learner with only a minimal command of the

system. In this sense, grammar is a liberating force.

Notional and attitudinal

meanings in grammar

The above examples illustrate how grammar is used to indicate differences

in ‘notional meaning’ (Batstone 1995)—that is differences in semantic

categories, such as time, duration, frequency, definiteness, etc. The

liberating power which grammar gives us—to transcend the limitations of

lexis and context in the communication of meaning—is also deployed in

expressing attitudinal meanings, such as approval, disapproval, politeness,

abruptness, and social intimacy or distance, etc. (Batstone op. cit., Larsen-

Freeman op. cit.). The following example from Batstone (ibid.: 197)

illustrates how a writer might deliberately contrast two tenses to indicate

approval and disapproval towards the respective subjects of the verb:

Smith (1980) argued that

freedom of speech was seriously maintained. Johnson (1983), though,

argues that

Commenting on this example, Batstone (ibid.: 198) suggests that the use of

the past tense

signals that Smith’s argument is no longer worthy of current

interest . . . it is (in two significant senses) passe´,

whereas the contrasting use of the present tense in the following sentence

shows that

Johnson’s argument is held to be of real and continuing relevance.

The writer is here using grammar to signal something about his attitude

to the ideas he is discussing.

Central to the notion of grammar as a liberating force is the view of grammar

as a communicative resource on which speakers draw to express their

intended meanings at both levels—the notional and the attitudinal. As such

the use of a particular grammatical structure is a matter of speaker choice.

As language users, we may wish to be very clear about what we want to say,

or deliberately ambiguous, or non-committal.Wemay wish to sound polite,

distant, direct, or even rude.Wemay wish to convey formality or informality

according to the context in which we are operating. To do all these things,

speakers use the linguistic resources which the grammar of the language

makes available to them: grammar is thus at the service of the language

user, and the teaching of grammar—especially if we wish to present

grammar to our learners as something which is liberating and

empowering—should aim to reflect this.

Focus on form and output

tasks

The kind of liberating force attributed to grammar so far lies in its intrinsic

nature—as a resource to enhance power and precision in the

communication of meaning. However, there is another sense in which

grammar might be termed a liberating force, and that is in its potential as

a focus of second language instruction to drive forward learning processes

and so help to liberate the learner from the shackles of the ‘intermediate

plateau’. There is a considerable body of evidence in second language

acquisition research (see, for example, Long 2001; Ellis 2005) to suggest

that a focus on form—that is, a focus on specific grammatical forms as they

arise in contexts of language use—is an essential ingredient ‘to raise the

ultimate level of attainment’ (Long op. cit.: 184). In particular, second

language researchers such as Swain (1995) and Skehan (2002) have

argued strongly that output tasks which are both system-stretching, in

that they push the learners to use their full grammatical resources, and

awareness-raising, in the sense that they allow learners to become aware

of gaps in their current state of interlanguage development, are crucial

elements in a pedagogy designed to provide the required focus on form.

One of the practical implications of the notion of teaching grammar as

a liberating force, therefore, would be in the design of production tasks

which challenge learners grammatically, and also lead them to notice gaps

in their knowledge of the target language system.

Three design features in

teaching grammar as a liberating force

From the foregoing discussion, I propose that an approach to teaching

grammar as a liberating force should include the following three

elements:

1 Learner choice

Given that the deployment of grammar in communication invariably

involves the speaker or writer in making a free and conscious choice

(notwithstanding the fact that having chosen a particular grammatical

structure there are conventions to observe regarding its acceptable

formation), the first element is that the learner must have a degree of

choice over the grammatical structures they use, and deploy them as

effectively as they can to match specific contexts and meet specific

communicative goals. In this respect, an emphasis on grammar as

a liberating force would favour a process rather than a product approach

to teaching grammar (Batstone 1994; Thornbury 2001), whereby learners

are not compelled to use a particular grammatical structure which has

been preselected for them—it would be difficult to conceive of grammar

being genuinely a liberating force if they were—but rather they choose from

their stock of grammatical knowledge to express the meanings they wish

to convey.

2 Lexis to grammar

If grammar liberates the language user by enabling him/her to transcend

the limitations of telegraphic speech (using lexical items alone), there

should be a progression from lexis to grammar both in the way language

and materials are presented to learners, and in the language we expect them

to produce. A grammar production task would typically require the learners

to apply grammar to samples of language in which the grammar has been

reduced or simplified, as typically found in notes of a meeting or

a newspaper headline, where the meaning content is conveyed primarily

through lexical items. Such tasks, where the learners are in effect asked to

map grammar on to lexis, involve a process known variously as

grammaticization (Batstone 1994) or ‘grammaring’ (Thornbury 2001). By

engaging in this kind of activity, learners experience the process of using

their grammatical resources to develop the meaning potential contained in

the lexical items and express a range of meanings which the words alone

could not convey. Such a process is not dissimilar to the processes involved

in first language acquisition whereby the child moves from communication

through telegraphic utterances involving strings of lexical items to the

gradual deployment of morphemes and function words. It is not, however,

a process promoted in traditional approaches to grammar teaching such as

the presentation–practice–production format, where the learners are

typically asked to move in the opposite direction—they begin with

a preselected grammatical structure, and then have to slot lexis into it.

3 Comparing texts and

noticing gaps

The third element in teaching grammar as a liberating force derives from

well-established principles of task-based pedagogy (for example,Willis

1996; Skehan op. cit.) and relates to the importance of allowing the learners

to focus on grammatical forms which arise from their communicative

needs, and in particular as a result of noticing gaps in their own use of

grammar. These gaps are noticed through a process of comparing their

output on a language production task with that of other learners or more

proficient users, for example, a sample text, or a written transcript of native

speakers doing the same task (Willis op. cit.). The focus on grammar is thus

‘reactive’ rather than proactive (Doughty and Williams 1998), because it

arises from the specific communicative needs which the learners discover in

the processes of doing the task, reviewing their performance and comparing

it with others. In this way learners experience the liberating potential of

grammar, not just to help them express their meanings in a particular

activity with greater precision, but over time, through a sustained

programme of comparing and noticing ‘gaps’ and differences, to enable

them to develop their proficiency and sensitivity in the target language to

increasingly more advanced levels.

Task types for teaching

grammar as a liberating force

Four task types which exemplify these different elements are discussed

below. At the outset, I should point out that I do not claim any originality

for them, since they all involve classroom activities which have been in use

for many years, particularly as exercises to develop writing skills. Indeed

some, I would suggest, have partially fallen into disuse. What I am aiming

to do here is to show how fairly standard techniques, which have stood the

test of time, can be revitalized and adapted to support a more contemporary

approach to teaching grammar.

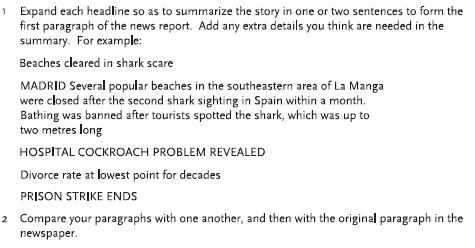

Task type 1:

Grammaticization tasks

In these tasks, the learners use their grammatical resources to develop and

expand information presented in the form of notes in which grammatical

features are reduced or even omitted altogether. The example in Figure 1

shows a grammaticization task using newspaper headlines, based on an

idea in Thornbury 2001. The three elements are clearly present in this type

of task: first, the learners have a free choice over which grammatical features

to use to expand the headlines, either individually or in consultation with

others; second, they start with lexis and add grammar to it, as well as any

additional lexis that may be required to develop and elaborate the story; and

third, after doing this, they compare their texts with one another and with

the original paragraph in the newspaper, and in this way naturally focus on

and discuss some of the differences between their use of grammar and that

of the original text, as well as differences in content. They can also be asked

to look for any patterns in the way grammar is used in the opening

paragraphs in all four stories, for example in the use of the present perfect

tense, relative clauses, clauses in apposition, and the use of the passive.

figure 1

Grammaticization task using newspaper headlines.

(Headlines 1,3, and

4 from The Times,

headline 2 from the

Ashford Express, Kent Messenger Group, 16

August 2007.)

Other grammaticization tasks, suitable for higher-level students—academic

writing classes, for example—could include the use of bullet points taken

from PowerPoint presentations prepared by the students themselves. These

would be used to ‘cue’ the writing of short paragraphs and summaries,

thereby giving practice in essay writing skills.

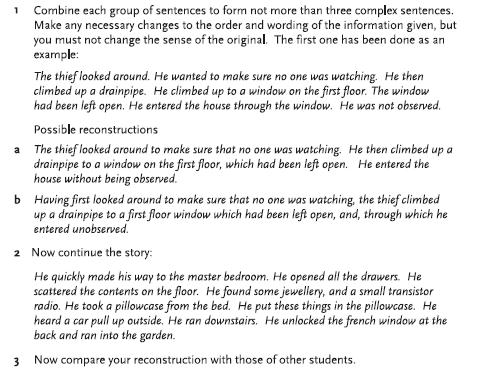

Task type 2: Synthesis

tasks

Synthesis tasks (Graver 1986) are variations on grammaticization tasks and

take the form of exercises which start with a short text, consisting of a string

of short, non-complex sentenceswhich the learners are required to combine

in some way so as to reduce the number of sentences and create a more

natural piece of text. The technique is a traditional sentence combination

task done at text rather than sentence level, and requires the use of various

grammatical devices needed for the construction of complex sentences,

such as relative clauses, purpose clauses and subordination, as well as

cohesive devices such as linking words. An example is given in Figure 2.

Again it will be seen that the task combines the three elements noted above:

the learners have choice over the grammatical devices they think are needed

to reconstruct the text in the most effective way, drawing on their own

knowledge of the language. They compare their versions with one another

and with the teacher’s own version and so have the opportunity to expand

their own knowledge. Finally, although the task may not, strictly speaking,

move from lexis to grammar, it certainly moves from a text where the

grammar has been artificially reduced or simplified to one in which it is

more elaborated. The task also develops sensitivity to writing style and what

makes a coherent, fluent narrative.

figure 2 Synthesis

task (adapted from an idea in Graver 1986)

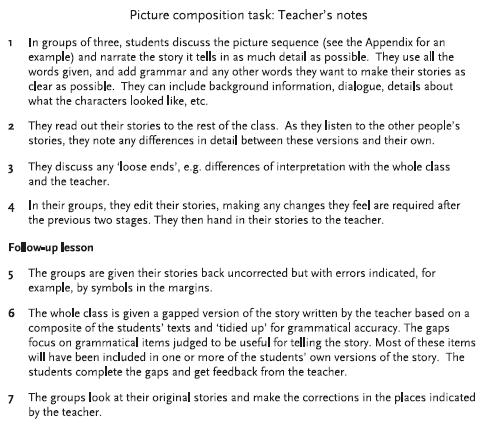

Task types 3 and 4:

dictogloss and picture composition

These two task types are variations on the same procedure, in that they

require the students to reconstruct an original ‘text’ by supplying more

grammar to it, and then comparing their new versions with those of

others. In dictogloss, or grammar dictation (Wajnryb 1990), learners

have to listen to and take notes on a short text read aloud to them, before

trying to reconstruct the text from their notes. Dictogloss clearly meets

all three criteria for designing tasks which emphasize the liberating

nature of grammar. The students move from lexis to grammar as they

strive to grammaticize the notes they made while listening to the text;

they choose from their own grammatical resources while reconstructing

the text; and finally they compare their versions with one another in order

to improve and refine them (Thornbury 1997), before comparing them

with the original version. A particular advantage of dictogloss is that the

texts selected (or specially written, as in Wajnryb’s 1990 book) can be of

any type—descriptive, narrative, argumentative, etc.—depending on

the aims of the lesson and needs of the learners. The example in the

Appendix is a paragraph from a Wikipedia entry about the Hubble

Telescope, which, if used with an upper-intermediate level academic

writing class, perhaps as part of a unit on space exploration, could lead to

a focus on various grammatical features such as the use of the present

perfect tense in descriptive texts of this kind, structures used with

superlative forms of adjectives, and word suffixes (astronomy, astronomer,

astronomical).

Picture composition is another traditional technique used in teaching

writing which lends itself to this approach to teaching grammar. In order

to provide for the ‘lexis to grammar’ dimension, the sequence of pictures

used would need to be accompanied by key words (provided either by the

teacher or ‘negotiated’ with the whole class). In addition, some language

can be built into the picture sequence itself, as is typically found in

a cartoon strip. The procedure shown in Figure 3 begins by following

a fairly traditional sequence (Steps 1 to 3) based on a similar task found

in

structured procedure for focusing on form at Steps 4 to 7, one which is

more consistent with the task-based cycle of teaching described by Willis

(op. cit.).

figure

I have made the element of comparing texts deliberately less direct

in this task, in order to avoid giving the students the impression that the

stories which they composed in Step 1 and edited in Step 4 are less worthy or

interesting than the other groups’ stories or the teacher’s ‘version’,

presented at Step 6. The teacher’s version in fact is only a composite of the

individual group versions (and it is important that it is presented as such)

andis available as a source for comparison at the end of the process when the

students correct any errors in their own

texts.

Conclusion

In this paper I have identified three elements which I see as being central to

an approach to teaching grammar which emphasizes its role as ‘a liberating

force’ (as defined in Widdowson’s essay), and have gone on to show how

these elements can be incorporated into the design of grammar production

activities in the EFL classroom. As has been pointed out, the approach

which these activities exemplify is task-based in design, in that the focus on

form comes after a freer activity in which the learners use whatever

language resources they can muster: the teaching progression is thus from

fluency to accuracy rather than vice versa. The activities also follow a process

approach to teaching grammar, in which grammatical items are not selected

and presented in advance for learners to use, but rather grammar is treated

as ‘a resource which language users exploit as they navigate their way

through discourse’ (Batstone 1994: 224). Gaps in their knowledge are

noticed later through the process of matching and comparing so that work

can begin on trying to fill them.

There are two further observations about the task types presented here

which need to be made. Firstly, given the scope of this paper, I have looked

only at types of task which require learners to produce language and have

not discussed receptive grammar tasks designed to raise awareness of the

various notional and attitudinal meanings which can be expressed by

grammar. Such tasks would involve considering the effects created by

changing some of the grammatical features used in a text, or asking learners

to make grammatical choices in a given text, for example, between active

and passive verb forms, and then comparing their choices with the original

text. Such awareness raising activities would also have an important role in

teaching grammar as a liberating force since they emphasize the notion of

learner choice in the use of grammar. Secondly, all the task types presented

have involved the learners in the creation of written texts, and are derived

from fairly standard guided writing tasks. This emphasis on writing is

deliberate: writing is generally done with more care and attention to

grammatical accuracy than speaking, while having a written text to study

and compare with another written text makes it easier to focus on form and

to notice and record features of grammar which might otherwise be

overlooked.

Finally, although I have argued in this paper that a process-oriented

approach to teaching grammar is more consistent with the notion of

grammar as a liberating force than a product-oriented approach, I am not

claiming that such an approach is inherently superior, and preferable at all

times and for all levels of student. There are many circumstances where it

may be necessary and desirable to pre-select language items for attention

prior to setting learners loose on a task, particularly for lower-level students,

and as a general policy a balanced combination of the two approaches is

likely to be the most effective teaching strategy to adopt. However, if we are

serious about emphasizing the notion of grammar as a liberating force in

our teaching, we need at least to provide opportunities for our learners to

experience its liberating potential through the kind of process-oriented

grammar tasks described here.

References

Batstone, R. 1994. ‘Product and process: grammar

in the second language classroom’ in M. Bygate,

A. Tonkyn, and E.Williams (eds.). Grammar and the

Second Language Teacher.

Prentice Hall International.

Batstone, R. 1995. ‘Grammar in discourse: attitude

and deniability’ in G. Cook and B. Seidlhofer (eds.).

Principle and Practice in Applied

Linguistics.

Doughty, C. and J. Williams. 1998. ‘Pedagogic

choices in focus on form’ in C. Doughty and

J.Williams (eds.). Focus on Formin ClassroomSecond

Language Acquisition.

University Press.

Ellis, R. 2005. ‘Principles of instructed second

language learning’. System 33/2: 209–24.

Graver, B. 1986. Advanced English Practice (third

edition).

Larsen-Freeman, D. 2002. ‘The Grammar of choice’

in E. Hinkel and S. Fotos (eds.). New Perspectives on

Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms.

Long, M. 2001. ‘Focus on form: a design feature

in language teaching methodology’ in C. Candlin

and N.Mercer (eds.). English Language Teaching in its

Social Context.

Skehan, P. 2002. ‘Task-based instruction: theory,

research and practice’ inA. Pulverness (ed.). IATEFL

2002:

Swain, M. 1995. ‘Three functions of output in

second language learning’ in G. Cook and

B. Seidlhofer (eds.). Principle and Practice in

Applied Linguistics.

Thornbury, S. 1997. ‘Reformulation and

reconstruction: tasks that promote noticing’. ELT

Journal 51/4: 326–35.

Thornbury, S. 2001. Uncovering Grammar.

Heinemann Macmillan.

Wajnryb, R. 1990. Grammar Dictation.

Widdowson, H. 1990. Aspects of Language Teaching.

Willis, J.

The author

Richard Cullen is Head of the Department of English

and Language Studies at

classroom discourse, teacher and trainer

development, and the teaching and learning of

grammar, with a particular interest in spoken

grammar. He has worked for the British Council on

teacher education projects in

Email: rmc1@cant.ac.uk

Appendix

1 Dictogloss text

Students are given the first sentence of the text. They have to ‘recover’ the

rest by taking notes as it is read aloud to them (twice) and then

reconstructing the text from their notes.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a telescope in orbit around the Earth. It is

named after astronomer EdwinHubble, famous for his discovery of galaxies

outside the MilkyWay and his creation of Hubble’s Law, which calculates

the rate at which the universe is expanding. The telescope’s position outside

the Earth’s atmosphere allows it to take sharp optical images of very faint

objects, and since its launch in 1990, it has become one of the most

important instruments in the history of astronomy. It has been responsible

for many ground-breaking observations and has helped astronomers

achieve a better understanding of many fundamental problems in

astrophysics. Hubble’s Ultra Deep Field is the deepest (most sensitive)

astronomical optical image ever taken.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubble_Space_Telescope

2 Picture composition material

(The sequence of pictures is taken from Ur 1988: 218)

ELT Journal Volume 62/3 July 2008; doi:10.1093/elt/ccm042 221

© The Author 2008. Published by

Advance Access publication March 15, 2008

The full

text of this article, along with updated information and

services

is available online at

http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/62/3/221

Email and

RSS alerting:

Sign up

for email alerts, and subscribe to this journal’s RSS feeds at

http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]()

2.- USING

THE SOCRATIC METHOD TO TEACH CULTURE IN EFL CLASSROOMS

Socratic Method:

Dialectic and Its Use in Teaching Culture in EFL Classrooms

By Servet Çelik

Menu

1. Introduction

2. Core Elements of the Socratic Method

2. 1. The Text

2. 2. The Question

2. 3. The Leader

2. 4. The Participants

3. Adoption of the Socratic Method in EFL Teaching: What to Consider?

4. The Socratic Method and Culture Teaching: Sample Questions

5. Conclusion

Bibliography

1. Introduction

There are few educators, if none at all, who have never heard of Socrates, the classical Greek philosopher (470-399 BC), although not many would be familiar with the specifics of the theory of knowledge he introduced that we instinctively utilize in certain aspects of our daily lives today. He called it dialectic, “the art or practice of examining opinions or ideas logically, often by the method of questions and answers, so as to determine their validity” (Ellis, 2003, p. 2), while most refer to it nowadays as the Socratic Method or Socratic Seminar, “a method to try to understand information by creating an in-class dialogue based on a specific text” (Ellis, 2003, p. 2).

The Socratic Method of teaching is founded on the stance that it is essential to facilitate students’ thinking for themselves, as opposed to merely providing them with the prescribed so-called valid, acceptable or correct answers. In this sense, the method “encourages divergent thinking rather than convergent thinking” (Adams, n.d., cited in Ellis, 2003, p. 1). Hyman (1970) states that “for Socrates the way to stimulate the memory is to ask questions, since these elicit responses which lead to the end in mind” and only “through questioning a person recalls the knowledge possessed by his immortal soul” (p. 67). As outlined by Ellis (2003), Socrates would pick and initiate a discussion on a distinct aspect of an attention-grabbing concern, and through the practice of exchange of ideas by means of a back-and-forth concentrated question-and-answer session, he would aspire to elicit one’s full knowledge (or lack of knowledge) and demonstrate the limits of the human mind. In this process, he himself would play dumb by pretending not knowing anything, and would follow a painstaking step-by-step model by expressing his hunger for wisdom through dialogue, during which he would make every effort to ensure that both parties are compelled to ask questions vis-à-vis reasoning, facts, connections, and examples to clarify, support, correct, modify, and/or change their ideas, as necessary, in light of new data. The closing of such profound and passionate conversations are regarded as openings for further inquiries, never as absolute conclusions, as the implied goal is meaning-making rather than mastering information.

Although Socrates’ foremost conviction, that “there is no teaching, only recollecting; learning is remembering” (Hyman, 1970, p. 58) and the belief that “he is demonstrating the method whereby memory is stimulated” (Hyman, 1970, p. 66), may not be welcomed by the educators of the millennium, the likely success and sensation the deliberate use of his method can bring to our modern, but at times tedious and inert, classrooms is worth giving a try. After all, one of the major criticisms of today’s teachers and schools is overloading the students with a superfluous bulk of information that is of no practical use in life, and their lack of promotion of the most crucial skills in students, such as higher order thinking and imagination, and the Socratic Method offers a resolution to such concerns as the students and teachers seek out a “deeper understanding of complex ideas through rigorously thoughtful dialogue, rather than by memorizing bits of information or meeting arbitrary demands for coverage” (Ellis, 2003, p. 2). Further, we, as the teachers of the new era, should feel accountable to create an eclectic or integrated way of teaching by making a conscious effort to exploit whatever it is that works for us in our milieu of teaching, and the Socratic Method may, for some, be one of the effective methods they can take advantage of.

Socrates might not believe in teaching, but in our understanding, he is teaching through his focused questioning, his own method of advancing critical thinking and invigorating memory, and furthermore, his technique depicts the indispensable characteristics and parts of what we desire and require in education to make efficient teaching and learning happen: having clear objectives and rationales in what we do, and a fitting routine to accompany them. Yet, his denial of teaching may actually make sense to today’s educators after careful consideration of the socio-cultural and educational context of his time; simply that education was regarded, by most, to be nothing, but a concrete entity people had to possess in order to gain prosperity and social status (which, by the way, may still be the case in 2007’s world where education and factual learning are believed to be equivalent to college degrees), and rote learning, repetition and chain drills (as in 1940’s Audio Lingual Method) were deemed to be the only intellectual ways of teaching. Thus, it may well be explicable for a wise man, who claimed he did not know anything, to relentlessly question others, who thought they knew everything, in an attempt to practice a mutual quest for the multifaceted truth and virtue, and ultimately, to refute the authenticity of the view of teaching at the time based on the letdowns of the so-called educated.

2. Core Elements of the

Socratic Method

According to Paul Raider (n.d., cited in Ellis, 2003), the Socratic Method is made of four key components: the text, the question, the leader, and the participants.

2. 1. The Text

The very first step to a thriving Socratic teaching is selecting the proper text. Texts can be chosen from a wide variety of resources such as, but not limited to, readings in social and physical sciences, movies, art works, and music. Especially at the beginning stages, they should be kept short to familiarize the students with the method, and to give them the confidence they need. Correspondingly, long texts for novel users of the Socratic Method can be exceedingly demanding and/or may lead to agonizing boredom. As the teacher and the students get more proficient using the method a few times, the teacher may start introducing slightly longer texts or may combine a few short ones to use at the same time. Regardless of their size, good texts are closely linked to the overall goals of the text, subject, unit, and the classroom; they are at an adequate level to activate the students’ minds, but not overwhelm them; and, they are rich in that they discuss a range of issues, offer different viewpoints, and stimulate critical thinking.

2. 2. The Question

The second central element in Socratic coaching is the preliminary question either the leader (teacher) or a veteran participant (student) poses. The beginning question to initiate the dialogue should be well-planned, and mirror an authentic thought-provoking inquest. Such a question should not endorse only one way of thinking or a preset correct answer, but should rather generate further speculation and hypotheses, and in due course, responses and explanations provided to it should lead to both new discoveries about the text and additional questions, and thus, to new responses, all emerging unpredictably on a whim. The secondary and supporting questions used not only by the leader, but also by the participants, to describe, illuminate or review what everyone brings to the table should also meet the basic criteria referred to above for opening questions, except that they may not be open-ended and can take different forms to elicit a number of aspects such as agreement/disagreement, clarification, support, comparison and contrast, questions, and personal experience. In brief, the type of questions chosen to ask has a direct impact on the end result, bearing in mind that “the crux of the matter, whether the result be [is] recollection or reasoning, is in the questions Socrates asks” (Hyman, 1970, p. 67).

2. 3. The Leader

The leader, the next chief constituent in Socratic instruction, is typically the teacher, who not only guides the discourse, but also takes an active part in it. The teacher should feel the same enthusiasm and inquisitiveness about the text, and about the method alike, as are required of the students, for a triumphant Socratic teaching. A fine leader willfully keeps the dialogue on track by asking the right questions that help shed light on the topic, and by successfully modeling the Socratic perception, thinking and intelligence. Although it is not feasible, nor is it an objective, to predict each and every question that the participants may ask, the leader must become an expert on the text to be able to attend to different initiatives and ways of sorting out the unanticipated information put forward by different minds. The teacher should remember that there is a need to be patient with the students’ devising, organizing and transforming their ideas during the somewhat lengthy process of nonstop questioning, and should be tolerant of any likely conventional and rigid thinking practices the students may demonstrate every now and then. Furthermore, the teacher should keep tabs on the students’ progress, and establish equilibrium between the students by making a conscious attempt to engage the reluctant participants during the channel of communication, while limiting the ones who routinely have their voices heard.

2. 4 The Participants

The last, but not least, requisite affiliate in implementing the Socratic debate is the participants who the successful completion and quality of the procedure heavily rely on. While we refer, by and large, to the students as the participants, teachers can, and should, be viewed as active partakers in that process as well. The participants should attentively study and analyze the texts ahead of time, and be prepared and willing to contribute to the exchange of ideas by practicing active-listening, communicating their position, constantly reflecting on their reasoning, and reformulating their ideas. Since the Socratic Method counts, first and foremost, on dialogue, and dialogue involves a variety of skills that can be taught and learned, the teacher and the students can reminisce about their previous session and discuss what can be done to improve the use of this method next time, and they can practice, in addition to reading, listening, thinking, and discussing, an assortment of affective skills such as suspending their biases and stereotypes, being respectful and tolerant of others and diverse ideas, and being open to change for personal growth. Teachers should reinforce the conception that the aim is not to locate the right answers, but instead, to explore important issues and to construct well-supported ideas through a joint effort, which will, in turn, hearten the students to share their minds openly and to fairly evaluate others’ views. Such collaboration and attitude fosters active learning, and also serves as a way to bond and build a positive relationship between the teacher and the students, which ultimately is beneficial to the success of the classroom.

3. Adoption of the

Socratic Method in EFL Teaching: What to Consider?

Although “Socrates claimed that the Socratic method was not a teaching method but rather a method of philosophical inquiry, a way of seeking wisdom” (Hyman, 1970, p. 77), it can well be successfully implemented in all areas of education including EFL teaching. However, certain aspects of this method do not adhere to the humanistic language teaching practices that are of high value in contemporary language education, and need to be revised. As Hyman (1970) suggests, “the question is, then, what to modify in the Socratic method in order to convert it into a teaching method” (p. 78).

The primary troubling element the Socratic thinking incorporates, that we should be alert to, is the potential chaos and turmoil it is likely to fabricate due to its intense and potentially infuriating nature. Oliver and Shaver (1966), for instance, in a study of classroom discourse, uncovered the frightening truth that the Socratic Method can provoke negative emotional responses in students such as, but not limited to, disappointment, aggravation, stress, anxiety, and anger. Thus, several actions need to be taken to alter or eliminate the underlying causes of such dangerous reactions, all of which may severely limit the students’ learning and the quality of our classrooms. All in all, the teachers’ responsibility is to create an environment of competition, tolerance, and fun all at the same time, not a battlefield of harsh feelings or malicious encounters.

Hyman (1970) suggests several ways of abolishing the potential risks associated with the Socratic Method that have been mentioned above. Initially, unlike the field of Law where this method has been frequently used to overpower the individuals for the sake of finding the truth, the field of Education calls for special care, compassion and kindheartedness to establish a mutual understanding, trust and respect between the teacher and the students. This is particularly important in the case of foreign language learners who may already be feeling marginalized due to being forced to study a foreign language and its culture (i.e., compulsory EFL classes). Therefore, the teachers must ascertain that the students are not put down or dejected, but instead are inspired and fueled, throughout the questioning. Otherwise, the teachers using the Socratic Method for instructional diversity and excellence would turn into magnets of revulsion seeking to disclose their students’ weaknesses and lack of knowledge to talk them into their own way of thinking.

According to Hyman (1970), in serving the purpose elucidated here, namely reducing the tension linked to the Socratic practice, teachers are advised to carry out three specific tasks. Initially, the teachers should keep the use of this method brief, as 10-15 minutes would be enough to arouse curiosity in a topic, and to practice critical thinking and sharing of ideas, without making the students feel like alleged suspects of a crime desperately being questioned. Secondly, the teachers can use humor and jokes to decrease the pressure that the Socratic questioning may result in, as inserting comedy in the dialectic may help balance the downsides of this method. Next, the students should be encouraged to concentrate on the characterization of the ideas, facts, and the meanings attached to them, as well as on the progression of their thinking, while their attention is diverted from the uncertainty and insecurity they may experience. Lastly, the teachers should realize that the Socratic Method is complex and sluggish in nature, as it requires a string of questions, each of which serves to bring forth the preceding responses before moving forward; thus, they should not rush the students, and persevere gradually, which can eventually help trim down periodically the students’ likely unease.

The next type of modification desired in the Socratic Method, as Hyman (1970) affirms, “involves the outcome of the dialogue” (p. 80). Unlike Socrates’ fellows who felt defeated and distraught at the end of the interchange, the end result we wish to produce by using this method in teaching is to create a sense of satisfaction and success in our students, or at least an impermanent feeling of relief and value. Yet, this may not be an easy task to accomplish, particularly at the early stages of the utilization of the method when the teachers keep the length of its operation short to lessen the latent negative effects. In any case, we should endeavor to create some sort of meaning so that the students will not feel worthless, distorted or lost, and whether they wind up having a resolution and breakthrough or not at the end, they will feel the need to clarify and/or inquire further.

Once these recommended changes and measures are executed, the Socratic Method can be used to successfully cover a variety of topics in teaching. However, one should recognize that this method is not as straightforward as it may come across, and that its practice requires numerous skills, meticulous preparation, intellectual strength, unremitting vigilance, and a never-ending patience. Considering the fact that the substance and direction of the dialogue is not known to the teachers in advance, it is crucial that the teachers understand the core qualities of the Socratic Method, and that they carefully analyze and grasp the essence of the chosen topic, put their superior inquiry and assessment skills into practice, persistently monitor their students’ cognitive progress and affective reactions, and systematically advance the students’ higher order thinking skills and adaptation of their ideas. Absence of the essential knowledge and expertise required of the leaders in Socratic teaching carries the risk of turning the exhausting dialogical trade, and the class time, into a “meandering bull session of little value” (Hyman, 1970, p. 80).

As a final point, the teachers should establish a fair, inventive and enriching assessment system, rather than using long-established stringent grading based on the students’ performance in the Socratic debate. The teachers should recognize that some type of formal evaluation should accompany the method’s implementation for pedagogical purposes, as the students would then hit upon an educational rationale for it, and would be less likely to cultivate the delusion to see the Socratic Method as a way to dispute and appeal to the teacher figure, to their peers, and to the ideas that are different than their own. On the other hand, a view of this method as just another grading scheme may be perilous, as the dialogue and debate then turns into a testing session and/or discussion, and this may eliminate the very constructive outlook and purpose the method advocates. Therefore, a fine line between an effortless and practically nonexistent assessment procedure and a strict and damaging evaluation protocol should be established. The assessment criteria may be based on a rubric teachers can devise from a variety of print and/or online sources, or on a measure teachers and students can jointly write out after deliberation. Alternatively, in classrooms where student-centrism is of utmost importance, a self-assessment list or a seminar reflection questionnaire/survey can be employed.

The Socratic Method, even with the suggested alterations, may not work well with each and every student group. A certain level of intellect and proficiency in the content area (English, in this case) is needed. For instance, this method may not be feasible for learners of English at lower levels, unless it is wholly simplified, which might then fail to trigger the students’ thinking, or even if it might not, it could well be troublesome for the students to provide sharp expositions to issues highlighted in the dialogue. Similarly, additional modifications may be needed to use this method with young learners. As much as children demonstrate the type of passion and curiosity we desire in Socratic teaching, they lack the autonomy, patience, self-control and maturity that one should not disregard to properly handle the use of this method. With this being said, a capable group of students with the preferred proficiency and cognitive/maturity level does not necessarily guarantee success either. Thus, it is critical that the teachers are exceptionally familiar with their students, the richness of their life experiences, and their fervor for such a method so as to make an informed decision about whether this would expand their knowledge and perspective. Correspondingly, although the Socratic Method may benefit their students to a great extent, the teachers should avoid using it too often due to its tremendously demanding and lingering nature, which may enervate both the leader and the participants, and wipe out their craving for this method. Extended dialogues also have the potential to bring about dullness and to lead to distraction and dislike. Hence, replacing and/or blending it with other methods from time to time can greatly increase its reaching and the odds of obtaining better outcomes.

4. The Socratic Method

and Culture Teaching: Sample Questions

The definition of culture and the significance of culture teaching in EFL have been discussed in innumerable studies over the years. Thus, this section will not attempt to scrutinize what culture is (i.e., culture vs. Culture, or little c vs. big C, see Seelye, 1984) or why it is important for us, as teachers, to integrate it into foreign language instruction. The scope, therefore, will be limited to providing a list of sample questions that can be used to teach the target language culture through the Socratic Method so that language learners’ understanding and appreciation of the conventional behavior of native speakers of English in various situations (i.e., personal space, eating habits, music, and literature) can be accomplished.

It is vital that teachers, before initiating a Socratic seminar, dwell vigilantly on the type of issues concerning teaching culture that they would like to explore and illustrate. Students’ feelings and attitudes toward the target language cultures (i.e., potential stereotypes), and possible effects of their points of views on their own language learning practices and process may be just two of the myriad promising topics EFL teachers may consider conveying in their classrooms. Whatever topics they end up settling on, the teachers should be aware of the magnitude of picking the best questions to raise, as one of the basic principles of the Socratic method, as mentioned earlier, entails that teachers should not ask questions they already have an answer to, nor should they bring in queries that will not inspire or fire the students (i.e., undemanding questions with straightforward answers). Reflecting back on the issues discussed throughout this paper, a list of questions, though not carved-in-stone and can be modified, extended or replaced, is provided below as a model. Yet, their application cannot be practiced on paper, and their use and success in a classroom would very much depend on the contextual factors including the enthusiasm and performance of those who are involved.

Questions

• How do different beliefs, ethics, or values influence people's behaviors and the society they live in? What factors can you think of that shape one’s worldview, values and beliefs?

• How would you describe culture? What are some of the things culture consists of?

• Why would we need culture? Do you think it is important? Can we not do without it? Can you provide some evidence to support your opinion?

• How does culture reveal itself in a society? What are some of the ways or channels through which culture can be characterized, practiced, and reproduced?

• Does culture show discrepancies across geographical regions, nations, countries, and so forth? If yes, why and how so? Are there also universal qualities between people of different cultures?

• Is any one culture simple, or better or worse than others? What is some evidence for your view?

• What are some of the potential conflicts that are likely to occur due to lack of knowledge of the cultural differences when people of different cultures and norms meet up?

• What safety measures can be performed to prevent or reduce cultural misunderstandings and clashes, and their potential negative effects?

• Can you think of ways of how one would discover and gain knowledge of others’ cultures? What would you do if you were to learn about another culture?

• What are some of the practices associated with your own culture? Do you find them all appealing, or are there things that you are not fond of about your culture?

• When people from other countries think about your culture, what do they usually think of? What are some things they may wonder about?

• What is the best/most important thing your culture has given to the world? What is the best/most important thing your culture/country has adopted from another culture?

• If a group of people came to your country from overseas, what advice would you give them? What do you think would surprise them? How do you think they would feel during their stay in your country?

• What would you like to know about a different culture before you traveled to a different country? How would you feel if you left your home culture and entered into a completely new culture?

• What

do we mean when we say “When you are in

• How is language related to culture? Why would one need to learn about the culture of the native speakers of a language being studied?

• Have you searched for any information regarding native English speakers’ cultures through books, the Internet, or other sources? What did you discover? In what ways were they alike or different from those of your own culture? What would you like to know about their culture that you have not explored yet?

• Would you ever consider marrying a native speaker of English, or living permanently in an English speaking country? If yes, why; If no, why not? If you would, how would an intercultural awareness and cultural acceptance play a role in your experiences?

5. Conclusion

Socratic practice lets us see that the best way to attain consistent and long-lasting knowledge is through the practice of disciplined and persistent questioning (dialectic), making this method a form of theoretical skepticism and critical thinking, with teachers asking rather than telling. Questioning, in this sense, is more than a technique used solely to satisfy our nosiness, and should be viewed as an opportunity to learn about being “critical in the sense of being open to what we do not know, open to the possibility that we think we know more than we do, and paradoxically, that we know more than we assume and know more than we adequately express in public dialogue” (Elkins, 1990, p. 243).

In an EFL context, the students may sometimes detach themselves from the language being studied when they are outside of the classroom, because they may either have only few, if any at all, opportunities to practice what they study in class once the class time is up, or simply lack the motivation needed to further review, practice and reinforce what has been learned. This second assumption, the hard-to-maintain prolonged stimulation, is particularly the case when the students are required to study English as a mandatory subject against their will, and this dilemma is doubled when affective factors such as moral issues, values, and beliefs attached to the English-speaking populations, to the target language culture in general, are included in the language study. In an attempt to prevent the possible resistance from the students who may, at times, feel that their home culture is being attacked and English is being introduced as a replacement, the teachers need to conceive a thriving method to effectively cover the habitually sensitive cultural material, and Socratic dialogue may be a hard-to-find exemplar. However, one should keep in mind that elicitation efforts and methods during Socratic questioning should not be seen or used as a means of endorsing a teacher-centered classroom, but should serve as a way to bring about the students’ voices (Conlon, 2005). Only then, such dialogue can motivate the learners to think and work collectively with the teacher so as to wash out their preconceptions and delusions, and to facilitate their cultural learning.

In conclusion, an appropriate use of the Socratic Method tailored to the needs of our particular contexts in EFL teaching can provide the students with opportunities for critical study of cultural texts, active learning of the target language culture through a well-versed dialogue, the acquisition of an intercultural awareness through mutual respect for others and their ideas, and by and large, a positive learning environment where a prevailing community of inquiry is built and collaborative effort is celebrated. It gives the students and teachers involved not a sense of closure at the end of the class, but a taste of a cultural festivity that the participants would hope would never end and will look forward to returning back to.

Bibliography

Conlon, S. (2005). Eliciting students’ voices in the Thai context: A routine or a quest? ABAC Journal, 25(1), pp. 33-52.

Elkins, J. R. (1990). Socrates and the pedagogy of critique. Legal Studies Forum, 14(3), pp. 231-252.

Ellis, J. (2003, June). Socratic seminars: Creating a community of inquiry. Retrieved March 10, 2007 from http://web000.greece.k12.ny.us/tlc/Socratic%20Seminars/GRTCN%20Socratic%20Seminars.pdf

Hyman, R. T. (1970). Ways of teaching.

Oliver, D. W., & Shaver, J. P. (1966).

Teaching public issues in the high school.

Seelye, N. H. (1984). Teaching culture:

Strategies for intercultural communication.

About the Author

Servet Çelik, a Ph.D candidate in Language

Education at

Humanising Language Teaching

Year 9; Issue 5; September 2007, ISSN 1755-9715

© 2007 by Humanising Language Teaching

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]()

3.- TEN HELPFUL IDEAS FOR TEACHING ENGLISH TO YOUNG

LEARNERS

Ten Helpful Ideas for

Teaching English to Young Learners

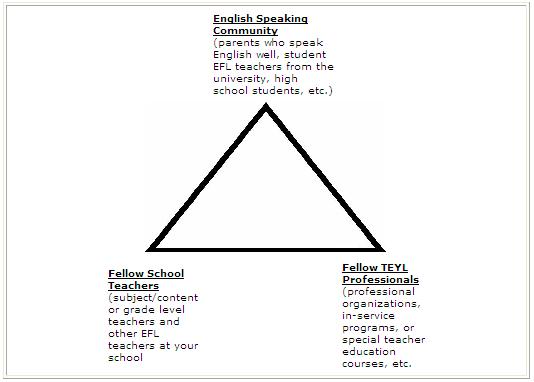

By Joan Kang Shin

Teaching English to Young Learners (TEYL) has become its own field of study as the age of compulsory English education has become lower and lower in countries around the world. It is widely believed that starting the study of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) before the critical period––12 or 13 years old––will build more proficient speakers of English. However, there is no empirical evidence supporting the idea that an early start in English language learning in foreign language contexts produces better English speakers (Nunan 1999). Levels of proficiency seem to be dependent on other factors––type of program and curriculum, number of hours spent in English class, and techniques and activities used (Rixon 2000). If an early start alone is not the solution, then what can EFL teachers of young learners do to take advantage of the flexibility of young minds and the malleability of young tongues to grow better speakers of English? As the age for English education lowers in classrooms across the globe, EFL teachers of young learners struggle to keep up with this trend and seek effective ways of teaching.

This article contains some helpful ideas to

incorporate into the TEYL classroom. These ideas come from the discussions and

assignments done in an online EFL teacher education course designed for

teachers, teacher supervisors, and other TEYL professionals. The participants

in the online course came from a number of different classroom situations and

countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, and

To clarify for whom these ideas are targeted, it is important to define young learner. The online course used the definitions provided by Slatterly and Willis (2001, 4): “Young Learners” (YL) were 7–12 years old; “Very Young Learners” (VYL) were defined as under 7 years of age. Although the online course was designed to train teachers of young learners, participants discussed ideas related to their teaching situations, which focused on both YLs and VYLs. Therefore, the ideas given below can be applied to learners ranging from approximately 5 to12 years old and can be used for various proficiency levels.

1. Supplement

activities with visuals, realia, and movement.

Young learners tend to have short attention spans and a lot of physical energy. In addition, children are very much linked to their surroundings and are more interested in the physical and the tangible. As Scott and Ytreberg (1990, 2) describe, “Their own understanding comes through hands and eyes and ears. The physical world is dominant at all times.”

One way to capture their attention and keep them engaged in activities is to supplement the activities with lots of brightly colored visuals, toys, puppets or objects to match the ones used in the stories that you tell or songs that you sing. These can also help make the language input comprehensible and can be used for follow-up activities, such as re-telling stories or guessing games. Although it may take a lot of preparation time to make colorful pictures and puppets or to collect toys and objects, it is worth the effort if you can reuse them in future classes. Try to make the visuals on thick paper or laminate them whenever possible for future use. Sometimes you can acquire donations for toys and objects from the people in your community, such as parents or other teachers. A great way to build your resources is to create a “Visuals and Realia Bank” with other teachers at your school by collecting toys, puppets, pictures, maps, calendars, and other paraphernalia and saving them for use in each other’s classes.

Included with the concept of visuals are gestures, which are very effective for students to gain understanding of language. In addition, tapping into children’s physical energy is always recommendable, so any time movement around the classroom or even outside can be used with a song, story, game, or activity, do it! James Asher’s (1977) method, Total Physical Response (TPR), where children listen to and follow through physical responses a series of instructions by the teacher, is a very popular method among teachers of young learners. This popular method can be used as a technique with storytelling and with songs that teach language related to any kind of movement or physical action. Children have fun with movement, and the more fun for students, the better they will remember the language learned.

2. Involve students in

making visuals and realia.

One way to make the learning more fun is to involve students in the creation of the visuals or realia. Having children involved in creating the visuals that are related to the lesson helps engage students in the learning process by introducing them to the context as well as to relevant vocabulary items. In addition, language related to the arts and crafts activities can be taught while making or drawing the visuals. Certainly students are more likely to feel interested and invested in the lesson and will probably take better care of the materials (Moon 2000).

You can have students draw the different animal characters for a story or even create puppets. For example, if the story is Goldilocks and the Three Bears, you may want to use puppets to help show the action of the story. To get students more excited about the story, have them make little pencil puppets of the three bears and Goldilocks before the storytelling. It’s a nice little art project that doesn’t have to take up too much time. If your students are too young to draw well, make copies of the characters on paper and have students color the characters and cut them out. The cut-out paper pictures can be taped to their pencils. After the storytelling, you can use the puppets to check comprehension of the story plot and have students practice the language by retelling the story using their puppets.

If you cannot spare the time in class to make the visuals you want to use, another idea is to consult the art teacher at your school (if you have one) and combine your efforts. If the art teacher is making some objects, pictures, or puppets, you could ask the teacher to make them for use in a particular storytelling or game in your class. Then, when students come to English class, they will bring their art projects to use. In addition, before the lesson, you can warm up by having students explain in English what they made in art class.

Some activities could use objects, toys, stuffed animals, or dolls. A “show and tell” activity is a perfect way to get students interested in the lesson with their own toys. The introduction to the lesson could be a short “show and tell” presentation that gives students a chance to introduce their objects in English. After this activity, get right into the lesson using the objects the students brought in.

3. Move from activity

to activity.

As stated before, young learners have short attention spans. For young students, from ages 5 to10 especially, it is a good idea to move quickly from activity to activity. Do not spend more than 10 or 15 minutes on any one activity because children tend to become bored easily. As children get older, their ability to concentrate for longer periods of time increases. So for students ages 5–7, you should try to keep activities between 5 and 10 minutes long. Students ages 8–10 can handle activities that are 10 to 15 minutes long. It is always possible to revisit an activity later in class or in the next class.

For example, if you are teaching a song or telling a story, don’t stay on that song or story the whole class time. Follow up the song or story with a related TPR activity to keep the momentum of the class going. Then have students play a quick game in pairs. As shown in this brief example, varying the types of activities also helps to keep young learners interested. Scott and Ytreberg (1990, 102) suggest creating a balance between the following kinds of activities:

• Quiet/noisy exercises

• Different skills: listening/talking/reading/writing

• Individual/ pairwork/ groupwork/ whole class activities

• Teacher-pupil/ pupil-pupil activities

When teachers mix up the pace of the class and the types of activities used, students will be more likely to stay focused on the lesson, thereby increasing the amount of language learning in class.

4. Teach in themes.

When you plan a variety of activities, it is important to have them connect to each other in order to support the language learning process. Moving from one activity to others that are related in content and language helps to recycle the language and reinforce students’ understanding and use of it. However, moving from activity to activity when the activities are not related to each other can make it easy to lose the focus of the class. If students are presented with a larger context in which to use English to learn and communicate, then attainment of language objectives should come more naturally. Thematic units, which are a series of lessons revolving around the same topic or subject, can create a broader context and allow students to focus more on content and communication than on language structure.

It is a good idea to use thematic unit planning because it builds a larger context within which students can learn language. When teaching English to young learners this way, you can incorporate many activities, songs, and stories that build on students’ knowledge and recycle language throughout the unit. This gives students plenty of practice using the language learned and helps them scaffold their learning of new language. Common themes for very young learners are animals, friends, and family or units revolving around a storybook, such as The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle, which includes food and the days of the week. As children get older, units could be based on topics such as the environment, citizenship, and shopping, or based on a website or book relevant to them.

Haas (2000) supports the use of thematic unit planning for young foreign language learners by pointing out that “Foreign language instruction for children can be enriched when teachers use thematic units that focus on content-area information, engage students in activities in which they must think critically, and provide opportunities for students to use the target language in meaningful contexts and in new and complex ways.” A good way to plan a unit is to explore what content your students are learning in their other classes and develop English lessons using similar content. Look at the curriculum for the other subjects your students take in their native language (L1) or talk to your students’ other teachers and see if you can create a thematic unit in English class related to what you find.

5. Use stories and

contexts familiar to students.

When choosing materials or themes to use, it is important that you find ones that are

appropriate for your students based on their language proficiency and what is of interest to them. Because young learners, especially VYLs, are just beginning to learn content and stories in their native language in school and are still developing cognitively, they may have limited knowledge and experience in the world. This means that the contexts that you use when teaching English, which may be a completely new and foreign language, should be contexts that are familiar to them. Use of stories and contexts that they have experience with in their L1 could help these young learners connect a completely new language with the background knowledge they already have. Teachers could take a favorite story in the L1 and translate it into English for students or even teach the language based on situations that are found in the native country, especially if the materials the teachers have depict English-speaking environments that are unfamiliar to students.

This is not to suggest that stories and contexts from the target culture should not be used. Certainly one goal of foreign language instruction is to expose students to new languages and new cultures in order to prepare them to become global citizens in the future. However, teachers should not be afraid to use familiar contexts in students’ L1 in the L2 classroom. In fact, even when presenting material from the target, English-speaking cultures, it is always a good idea to relate the language and content to students’ home culture to personalize the lesson and allow students an opportunity to link the new content and language to their own lives and experience. Young learners are still making important links to their home cultures, so it is important to reinforce that even in L2 instruction.

6. Establish classroom

routines in English.

Young learners function well within a structured environment and enjoy repetition of certain routines and activities. Having basic routines in the classroom can help to manage young learners. For example, to get students’ attention before reading a story or to get them to quiet down before an activity, the teacher can clap short rhythms for students to repeat. Once the students are settled down, the teacher can start the lesson by singing a short song that students are familiar with, such as the alphabet song or a chant they particularly enjoy. Here is a chant with TPR that can get students ready to begin the class.

Reach up high! (Children reach their arms up in the air)

Reach down low! (Children bend over and touch their toes.)

Let’s sit down and start the show! (Children sit down.)

Look to the left! (Turn heads to the left.)

Look to the right! (Turn heads to the right.)

Let’s work hard and reach new heights!

The movements can be substituted to teach new words. For example, instead of “Look to the left! Look to the right!” the teacher can use “Point to the left! Point to the right!” Providing some variation can keep this chant engaging. Just remember to keep the ending since it starts the class on a positive note.

Add classroom language to the routines as well. When it’s time to read a story, the teachers can engage students in the following dialogue:

Teacher: It’s story time! What time is it, everyone?

Students: It’s story time!

Teacher: And… what do we do for story time?

Student: We tell stories!

Build on this language by adding more after students have mastered the above interaction. The teacher can follow up the previous interaction with: “That’s right! The story is called The Very Hungry Caterpillar. What’s the story called?” (Students answer.) Whatever the routine is, the teacher should build interactions in English around that routine. As Cameron (2001, 10) points out, “…we can see how classroom routines, which happen every day may provide opportunities for language development.” The example below illustrates how the teacher and students can have real communicative interactions in English using some classroom language.

Teacher: Good morning, class!

Students: Good morning, Ms. Shin

Teacher: Faida, what day is it today?

Faida: I don’t know.

Teacher: Okay, then ask Asli.

Faida: Asli, what day is it today?

Asli: Today is Tuesday.

Teacher: Good! And what is Tuesday?

Students: Tuesday is Storytelling Day!

Notice that the communication is real and that a routine has been established––that Tuesday is Storytelling Day. Once students become fluid with certain interactions, as in the example above, you can begin introducing more language into the daily routines.

7. Use L1 as a resource

when necessary.

Because many interpretations of various communicative approaches try to enforce the “English only” rule, teachers sometimes feel bad when they use L1. Teachers these days are mostly encouraged to teach English through English, especially at the younger ages. One reason is to give students the maximum exposure to the English language. Why not use L1? It is one quick, easy way to make a difficult expression such as “Once upon a time” comprehensible. After quickly explaining a difficult expression like that in L1, students will recognize the expression in English every time it comes up in a story. Since EFL teachers usually have a limited amount of time with students in many classroom situations, that time is too precious to waste. If it is more efficient to use L1 for a difficult expression or word, just use it. Concentrate on building communicative skills. Save your time for the target language that is actually within students’ reach. For words that students can figure out, the teacher can rely on visuals, realia, and gestures. Important in the decision to use L1 to translate new language is carefully defining the language objectives for the activities. The teacher should spend class time focusing on those target language objectives rather than spending time trying to make a difficult word or expression comprehensible in English.

In addition, some students who have very low proficiency can easily become discouraged when all communication in the classroom must be in English. Sometimes these students can express comprehension of English in their native language, and this can be acceptable for lower level students. However, whenever possible, take the answers in L1 and recast them in English. In addition, directions for many activities can be quite complicated when explained in the L2, so consider using L1 when it is more important to spend time doing the activity rather than explaining it. In short, use L1 in the classroom as a resource for forwarding the learning process without becoming too reliant on it.

8. Bring in helpers

from the community.