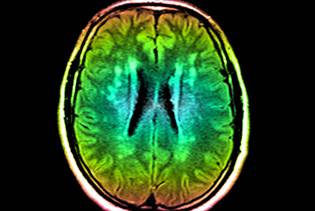

1.- THERE IS NO LEFT-BRAIN/RIGHT-BRAIN DIVIDE

You are hardly alone if you believe that

humanity is divided into two great camps: the left-brain and the right-brain thinkers — those who are

logical and analytical vs. those who are intuitive and creative. For years, an

industry of books, tests and videos has flourished on this concept. It seems to

be natural law.

You are hardly alone if you believe that

humanity is divided into two great camps: the left-brain and the right-brain thinkers — those who are

logical and analytical vs. those who are intuitive and creative. For years, an

industry of books, tests and videos has flourished on this concept. It seems to

be natural law.

Except, it isn’t.

Scientists have long known that the

popular left-brain/right-brain story doesn’t hold water. Here’s why. First, the

sweeping characterizations of what the two halves of the brain miss the mark:

one is not logical and the other intuitive, one analytical and the other creative.

The left and right halves of the brain do function in some different ways, but

these differences are more subtle than is popularly believed (for example, the

left side processes small details of things you see, the right processes the

overall shape). Second, the halves of the brain don’t work in isolation;

rather, they always work together as a system. Your head is not an arena for

some never-ending competition, the brain’s “strong” side tussling with its

“weak.” Finally, people don’t preferentially use one side or the other.

The roots of the left/right story lie

in a small series of operations in the 1960s and 1970s by doctors working with

Roger W. Sperry, a Nobel-laureate neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology. Seeking treatment for

severe epilepsy, 16 patients agreed to let the doctors cut the corpus callosum,

the main nerve bundle that joins the two halves of the brain. They found some

relief from these dramatic visits to the O.R. — and when they left the

hospital, they allowed Sperry and his team to study their cognitive

functioning.

Laboratory findings do not always make

their way into the popular culture, but these did, which provided an

unfortunate opportunity for misinterpretation of what was, in essence, a

limited set of experiments. In 1973, the New York Times

Magazine published

an article titled, “We are left-brained or right-brained,” which began: “Two

very different persons inhabit our heads … One of them is verbal, analytic,

dominant. The other is artistic …” TIME featured the left/right story two years

later. Harvard

Business Review and Psychology Today jumped

in. Never mind that Sperry himself cautioned that “experimentally observed

polarity in right-left cognitive style is an idea in general with which it is

very easy to run wild.” A myth spread.

Myths, of course, are a timeless way to

make sense of experience. In the search for meaning, people may create

simplified narratives. This is a reasonable strategy, but the

right-brain/left-brain narrative introduced misconceptions.

We have developed a new theory built on

another, frequently overlooked, anatomical division of the brain: into its top

and bottom parts. Among other things, the top part sets up plans and revises

those plans when expected events do not occur; the bottom classifies and

interprets what we perceive.

Based on decades of research, the

theory holds that this distinction can help explain why individuals vary in how

they think and behave. We all use both parts of the brain, but differ in how

deeply we may use each part. The key is the way the parts interact, not each

part by itself. Depending on the extent to which a person uses the top and

bottom parts, four possible cognitive modes emerge. These modes reflect the

amount that a person likes to devise complex and detailed plans and likes to

understand events in depth. (You can determine your own dominant mode with this test.)

This new approach avoids the pitfalls

of the left-brain/right-brain story for several reasons. The characterizations

of what each part does are based on years of solid research. We emphasize that

the two parts always work together — it’s the relative balance of how much

people use the two parts that determines each cognitive mode. And we stress that the parts of the brain don’t work alone

or in competition, but seamlessly together. In some ways this theory too is a

simplification, but one that brings more understanding. If there’s one thing we

do know, it’s that as a species, we are continually inclined to try to

understand what we encounter, even something as complex as the brain.

Kosslyn is a cognitive

neuroscientist and was professor of psychology at Harvard University for over

30 years; he now serves as the founding dean of the Minerva Schools at the Keck

Graduate Institute. Miller is an author, filmmaker and Providence Journal staff writer. They are

the co-authors of Top Brain, Bottom Brain: Surprising Insights Into How You

Think.

Powered by WordPress.com VIP