SHARE

An

Electronic Magazine by Omar Villarreal and Marina Kirac ©

Year 8

Number 174 24th March 2007

11,850 SHARERS are reading this issue of SHARE this week

__________________________________________________________

Thousands of candles can be lighted from a single candle, and the life of the

candle will not be shortened. Happiness never decreases by being SHARED

__________________________________________________________

Dear SHARERS,

This has been an incredible week. We checked our

mailbox several times a day (the whole family was on duty!) so that it didn´t

get clogged. What can we say but a big THANK YOU to all the well-wishers.

There were a few queries also about how to read the

“new” SHARE. We worked on that with our graphic designer and we hope that the

tiny “problems” like closing a link before opening a new link have now been properly

dealt with and access will be simplified.

Please bear in mind that we are still tinkering with

the technology of the new format, so should you have a problem reading this

issue of SHARE, do not hesitate to write to us.

We will be happy to make your reading (and filing!)

as smooth and pleasant as possible.

So keep us posted on the inconveniences and enjoy

this new issue.

Love

Omar and Marina

______________________________________________________________________

In SHARE 174

1.- The Role of Affective Factors in the Development of Productive Skills

2.- Classroom Blogging: two

fundamental approaches

3.- Advanced Vocabulary in Context: What we wear down-under!

4.- 10th

Latin American ESP Colloquium

5.- Octavas

Jornadas Nacionales de Literatura Comparada

6.- I

Congress of the Brazilian Association of University Teachers of English

7.- Seminarios de

8.- First Congress for Teachers of English in

Concepción del Uruguay

9.- III Simposio Nacional “Ecos de

10.- International Association

for Dialogue Analysis: III Coloquio Argentino

11.- Workshop on How

to teach English in Kindergarten

12.- Teacher Development

Workshops at LCI

13.- Online

Course: Adopting Pedagogies for Learners at a Distance

14.- 12º

Encuentro Internacional de Narración Oral "Narradores sin fronteras"

15.- A

Message from Susan Hillyard

16.- Tenth International Congress for Teachers of English

in

17.- Brain

Gym Workshop in

18.- Perú

TESOL e-magazine

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 1.- THE ROLE OF AFFECTIVE FACTORS

IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF PRODUCTIVE

1.- THE ROLE OF AFFECTIVE FACTORS

IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF PRODUCTIVE

SKILLS

Our dear SHARER Sergio Casas has sent us this paper to SHARE with all of you:

Role

of Affective Factors in the Development of Productive Skills

Jelena

Mihaljević Djigunović

Faculty of

Philosophy,

jmihalje@ffzg.hr

Introduction

In the

past, it was often considered that language learning was primarily linked to

the

learner’s cognitive abilities to understand, reproduce and create messages in a

way

intelligible to other speakers of that language. By now, however, not only

have the

competences been redefined, but it is commonly accepted nowadays that

during the

foreign language (FL) learning process both cognitive and affective

learner qualities

are activated.

Affect

Affective

aspects of FL learning are a complex area whose importance is now well

established.

The number of affective learner factors considered in research is on

the

increase. New learner emotional characteristics are emerging as potentially

important

in order to understand and explain the process of language learning.

Affective

learner characteristics started to be more systematically studied and

measured

rather late (from mid twentieth century). They were more difficult to

define and

measure because they seemed to be more elusive as constructs. Interest

in the

affective aspects of learning was prompted, among other things, when it

was

realised that the whole personality of the learner needs to be involved in

education

and that

learners do not automatically develop emotionally as they may intellectually.

Affect came to be considered as a very important contributing factor to success

in learning. Some even went so far as to stress that affect was more important than

cognitive learner abilities because without, say, motivation to learn cognitive

learner abilities would not even start to be engaged in the process of learning.

In the next

few subsections we will touch upon only those affective learner

characteristics

that we included in our research study. These are attitudes and

motivation,

anxiety and self-concept.

Attitudes

and motivation

The

importance of attitudes and motivation in FL learning is not questioned any

more.

Numerous studies (e.g., Dörnyei, 2001; Gardner, 1985; Lambert & Gardner,

1972;

Mihaljević Djigunović, 1998) have confirmed that it is not possible

to fully

understand

what happens in FL learning or to interpret research results without

taking them

into consideration. In fact, besides language learning aptitude, motivation

is

considered to be the best predictor of FL achievement.

In

contemporary theories of language learning, attitudes are taken as a basis

on which

motivation for learning is formed or established. Attitudes are commonly

defined as

acquired and relatively durable relationships the learner has to

an object.

Lambert and

attitudes

connected to language learning motivation: attitudes towards the community

whose

language is being learned; attitudes towards the FL classes, towards

the FL

teacher, towards language learning as such etc. While Lambert and

the FL

community and its speakers are the most responsible for FL learning motivation,

other researchers

(e.g., Dörnyei, 2001; Nikolov, 2002) stress that in FL learning contexts

attitudes towards different aspects of the teaching situation take

precedence.

Recent

trends in motivational research seem to be rooted in a broader perspective,

in what Dörnyei

(1994) describes as the language level, the learner level and the learning

situation level. Motivation is increasingly approached as a multifaceted construct

(e.g., Clément & Gardner, 2001; Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005; Dörnyei, 2005,

Dörnyei & Ottó, 1998, Ushioda, 2003), that is as a phenomenon that includes

trait-like, situation-specific and state-like elements and that changes during the

different stages of the language learning process. Also, like other individual difference

variables, motivation is nowadays seen as a learner characteristic that interacts

with other individual difference variables, as well as with contextual factors.

Anxiety

There are

different approaches to the phenomenon of language anxiety (Scovel,

1991).

According to one, it is essentially a manifestation of more general types of

anxiety

such as communication apprehension, test anxiety or of apprehensiveness

as a

personality trait. According to a different approach, language anxiety is quite

a distinct

type of anxiety. The fact that some of the first studies on the effect of

anxiety on

different

types of anxiety. While it is true that conceptual foundations for the

phenomenon are provided by the concepts of communication apprehension, test

anxiety and fear of negative social evaluation, it is nowadays widely accepted that

language anxiety is “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs,

feelings,and behaviours related to classroom language learning arising from the

uniqueness of the language learning process” (Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope,

1991, p. 31).

MacIntyre

and Gardner defined it as ‘the feeling of tension and apprehension specifically

associated

with second language contexts, including speaking, listening and learning’

(1994, p. 284).

Determining

the causal direction in the negative relationship between anxiety

and

language achievement has engendered lively debate (Horwitz, 2000; MacIntyre,

1995a,

1995b; Sparks & Ganschow 1995, 2000). The basic issue has been

whether

anxiety causes poor performance or poor performance causes anxiety. On

the one

hand, the consistent negative relationship between language anxiety and

language

achievement in numerous studies has been explained as pervasive effects

of language

anxiety on cognitive processing (e.g., MacIntyre & Gardner, 1994). Anxiety

arousal is thought to be associated with self-related thoughts that compete

with task-related thoughts for cognitive resources. Due to the fact that information

processing capacity in humans is limited, the self-related cognition emerges as

a distracter or hindrance during cognitive performance. On the other hand, some

experts (Sparks & Ganschow, 1991, 1993, 1995, 2000; Sparks, Ganschow &

Javorsky, 1995) believe that language aptitude causes difficulties in

linguistic coding in L1 (particularly in the coding of its phonological and

syntactic aspects), which causes FL learning difficulties, which then give rise

to anxiety.

Anxiety,

like other affective variables, is then the consequence and not the cause of

poor FL

performance.

Self-concept

Another

learner factor we focused on in our study is self-concept. It is usually

defined

as a store

of self-perceptions that emerge through experiences and reflect the

perceived

reactions of other people (Laine, 1987). Authors usually distinguish the

following

three aspects:

the actual

self – a person’s notions, beliefs and cognitions of what he or she actually is

the ideal

self – what we would like to be, reflects our wants and aspirations, defines

our goals for the future; an optimal discrepancy may contribute to one’s motivation

the social

self – the way we perceive other people see us.

Aspects of

self-concept have been shown to be connected with learning achievement

(Burns,

1982; Sinclair, 1987). Self-concept changes with age (Wittrock, 1986).

It is also

related with attributions of success and failure in language learning. Ushioda

(1996) has stressed the great value of the ability of positive motivational thinking,

which helps the learner to maintain a positive self-concept in spite of negative

experiences during language learning.

Productive

language skills

Speaking

Most

learners consider speaking the most important language skill. Researchers

(e.g.,

Bygate, 2002) often describe it as a complex and multilevel skill. Part of the

complexity

is explained by the fact that speakers need to use their knowledge of

the

language and activate their ability to do this under real constraints.

Psycholinguistic

models of speech production, focusing on ways in which speakers plan and

monitor their speech production, recognize that variability is both socially

and psycholinguistically motivated. In Levelt’s model of speech production (1983)

the socially motivated variability is connected to message generation in the

‘conceptualiser’, while the psycholinguistically motivated sources of variability

are present at all levels: in the ‘conceptualiser’ (when speakers decide which

language variety to use and which communicative intentions they want to realize

through speech); in the ‘formulator’ (where the ‘pre-verbal message’ is turned

into a speech plan through word selection and application of grammatical and

phonological rules); in the ‘articulator’ (where the created speech plan is

converted into actual speech); and in the ‘speech comprehension system’ (which

offers speakers feedback on the basis of which they can make the necessary

adjustments in the ‘conceptualiser’).

It is

argued that while first language (L1) production is to a large extent

automatic, second language (L2) production in general is not. This is why

research on L2 variability has often concentrated on the effect of ‘planning

time’. It is assumed that, generally, L2 speakers need more time to plan the

processing stages and this is highly likely to affect L2 speech. During speech production,

speakers may pay conscious attention to different utterance elements so that

they could improve them.

A lot of

controversies still surround the teaching of speaking skills although a lot of

research has already been done on speaking both within the second language acquisition

field and theory of language teaching. Different approaches (Brumfit, 1984;

Littlewood, 1981; Skehan, 1998; Widdowson, 1998) to how the different parts of

the speaking skill hierarchy should be practised show that a lot more work

needs to be done before a general agreement is reached.

Writing

The

importance of writing in FL learning has been perceived differently throughout

history. In

the past it was only viewed, as Rivers (1968) nicely put it several decades

ago, as a handmaid to the other language skills, it was considered to be

useful for reinforcing the knowledge of vocabulary and grammar acquisition. It has

gone from not even being viewed as a skill which should be taught to a highly important

skill which gives us access to knowledge, power and resources. Recently,writing

has been recognized as a skill that is an important and compulsory part of FL

teaching for which teachers, as Silva (1993) points out, need more training in

order to teach well.

In the past

20 years or so, a number of authors (e.g,: Cumming, 1989; Raimes,1985; Zamel,

1983) have investigated various aspects of the writing skills. The most

relevant finding points to the need of reaching a threshold level of

proficiency in the FL before FL learners can engage the efficient processes

they use while writing in L1.

Study of

the relationship between affect and productive skills

The study

to be reported here was carried out as part of a national project called

English

in Croatia that

started in 2003. The project aimed to find out about the

communicative

competence levels Croatian learners of English as a foreign language

(EFL)

achieved by the end of primary and by the end of secondary education.

More than

2,000 learners’ competence was tested using communicative tests

developed

and validated in

validity

for the new context. The Hungarian tests were used because they were

considered

potentially valid for the Croatian context, due to many socio-educational

similarities,

and because the same tests would also allow comparisons between

the two

neighbouring countries.

The overall

findings of the project point to a good mastery of EFL by both primary

and

secondary school Croatian EFL learners at the level of the receptive

skills. In

listening comprehension and writing both primary and secondary school

participants

performed above the expected Council of

(CEFR, 2001) levels. The results for the

productive skills were, however, less impressive.

Below are

the general descriptors for the two levels of communicative

language

competence that Year 8 and Year 12 Croatian EFL learners are expected

to reach.

Year 8 learners are expected to be at the A2 CEFR level and Year 12

learners

should reach the B1 CEFR level.

A2

level:

Can understand

sentences and frequently used expressions related to areas of

most

immediate relevance (e.g. very basic personal and family information, shopping,

local

geography, employment). Can communicate in simple and routine

tasks

requiring a simple and direct exchange of information on familiar and routine

matters.

Can describe in simple terms aspects of his\her background, immediate

environment

and matters in areas of immediate need. (CEFR, 2001, p. 24).

B1

level:

Can

understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters

regularly

encountered

in work, school, leisure, etc. Can deal with most situations likely

to arise

whilst travelling in an area where the language is spoken. Can produce

simple

connected text on topics which are familiar or of personal interest. Can

describe

experiences and events, dreams, hopes and ambitions and briefly give

reasons and

explanations for opinions and plans. (CEFR, 2001, p. 24)

14 UPRT

2006: Empirical studies in English applied linguistics

During the

testing of communicative language competence, learners’ affective

characteristics

were also measured and this allowed a look at the relationship of

affect and

development of productive skills.

Aim of the

present study

The aim of

the present study was to look into the relationship of affective learner

characteristics

and development of speaking and writing competence of Croatian learners of EFL.

Although many studies have been carried out in order to see the relationship of

affect and language achievement, most have considered success in language

learning as a general construct including all the skills. It is our belief that

it might be useful to look into this relationship differentially, since

language learners are often stronger in some skills than others.

By considering

this relationship in Year 8 and Year 12 we hoped to not only get an insight

into the relationship itself, but also to be able to conclude about the development

of speaking and writing skills with reference to affect.

Participants

A total of

2,086 EFL learners participated in the study. There were 1,430 Year 8 and

656 Year 12

participants. These two years were chosen as they represent the

school-leaving

years. Year 8 is the final year of primary education in

when

students transfer to secondary education or leave the education system

altogether.

Year 12

marks the end of secondary education after which students look

for a job

or go on to the university. The Year 8 sample was drawn from village,

small town

and big town schools. Year 12 participants came from small and big

town

schools. The number of learners that took part in various parts of the testing

varied,

though, since the testing was done in three turns per class. Their

communicative

competence

in English was tested by means of a battery of tests consisting

of two test

booklets (one on reading comprehension and one on listening comprehension

and

writing) and a speaking test.

Instruments

Measures of

affect

In order to

collect data on the affective profile of learners a 13-item questionnaire

(see

Appendix) was used. Each item was accompanied by a 5-point Likert scale.

The

instrument was designed and validated in

before it

was used in the project. The 13 items elicited information on the following:

attitudes

to English, attitudes to EFL classes, motivation, self-concept and language

anxiety.

The scale was homogeneous, with ά = .833 and ά= .787 for Year 8

and Year 12

respectively.

Measures of

speaking skills

The oral

tests consisted of three tasks. The first two tasks were the same for both

groups of

participants.

Task 1

lasted 2-3 minutes and consisted of the interlocutor asking nine questions:

the first

three were general questions (What's your name? Could you spell your

name,

please? How old are you?), the other six could be selected from the remaining

nine. In

Task 2 participants were first to choose one of six pictures spread out on

the table,

describe it and explain the similarities and differences between the scene

in the

picture (e.g., a busy street, a garden) and the same place in their own life.

The task

lasted 4-5 minutes.

In Task 3,

which also lasted 4-5 minutes, Year 8 participants were to choose

two of six

situations and act them out with the interlocutor. For example:

Your friend

is coming to visit you. Give him/her directions from the nearest station

or bus stop

to your home.

You would

like to cook something nice with your friend. Discuss what you like or

dislike and

why.

In the

first situation the interlocutor initiated conversation, while in the second

one the

interviewee was to initiate it.

In their

Task 3, Year 12 participants were asked to choose one of five offered

statements

and say why they agree or disagree with it. The statements referred to

issues

(e.g., using mobile phones or watching soap operas) that young people have

strong

feelings about.

The oral

test was administered to six students from each school. The interlocutors

were

trained prior to going to the schools. The interviews were carried out

individually and audiotaped. The test lasted for up to 15 minutes and was strictly

structured timewise.

Measures of

writing skills

Year 8

participants were asked to describe two pictures by writing about the ten

differences

in the pictures. Prompts were given on what to describe.

Year 12

participants were asked to write a letter to the editor of a youth magazine

and give

reasons why their friend should get the best friend award. The letter

was

supposed to include about 150 words and there were five subtopics that had

to be

included.

Procedure

Writing

tests were administered to whole classes, while oral tests were done on an

individual

basis, out of class, and with only six students randomly chosen from

each

school.

Assessment

of speaking and writing performance was done by means of specially

designed

assessment scales. The speaking assessment scale was constructed

along the

following criteria: task achievement, vocabulary, accuracy and fluency,

pronunciation

and intonation. The scale included five bands (0-4). The writing

assessment

scale comprised the following criteria: task achievement, vocabulary,

accuracy

and text structure. There were five bands, four of which included double

scores (0,

1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-8).

The

assessors of both writing and speaking were trained. Since such training

has to

focus on the actual tasks, four sets of training (two for speaking and two for

writing)

were conducted. Length of the training depended on how much time the

assessors

needed to standardize their criteria.

Results

In this

section we will first present descriptive statistics for measures of affect,

speaking

skills and writing skills. Then we will look into correlations between

affect and

the assessed aspects of speaking and writing.

Descriptive

statistics

The

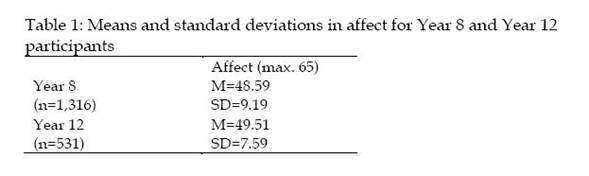

affective profile of the two age groups of participants did not show much

difference. Both groups tended to be positive about EFL learning and about

themselves

as language

learners (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Means and standard deviations in affect for Year 8 and Year 12

Table 1:

Means and standard deviations in affect for Year 8 and Year 12

participants

The means

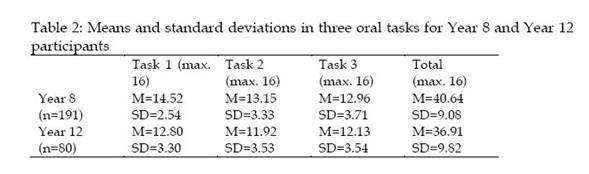

on orals tests show that Year 8 participants scored highest on Task 1

and lowest

on Task 3, while Year 12 participants also scored highest on Task 1 but

lowest on

Task 2, as presented in Table 2. Overall, younger participants showed

better

results on the speaking test.

Table 2:

Means and standard deviations in three oral tasks for Year 8 and Year 12

participants

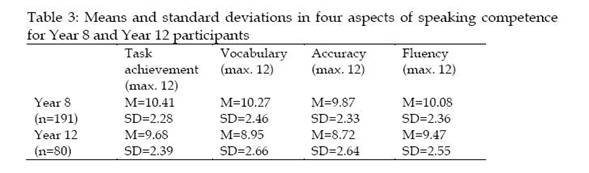

In terms of

the assessed aspects of EFL oral competence (Table 3), both groups

scored

higher on task achievement and fluency than on vocabulary and, particularly,

than on

accuracy. Year 8 participants scored higher on all the four aspects

than Year

12 participants.

Table 3:

Means and standard deviations in four aspects of speaking competence

for Year 8

and Year 12 participants

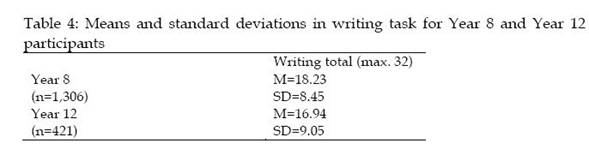

Year 8

participants showed a higher total score on the writing test than Year 12

students,

as Table 4 shows.

Table 4:

Means and standard deviations in writing task for Year 8 and Year 12

participants

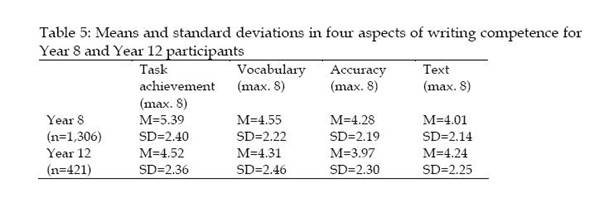

As can be

seen in Table 5, Year 8 participants were best at task achievement and

worst at

composing the text. While Year 12 participants also scored highest in task

achievement,

their text composing skill was not the least developed aspect of their

writing

skills; the biggest problem for them was accuracy.

Table 5:

Means and standard deviations in four aspects of writing competence for

Year 8 and

Year 12 participants

4.5.2 Correlations

Correlation

coefficients were computed between scores on the affect measure and

on the

speaking and writing tests and the individual aspects of the two skills.

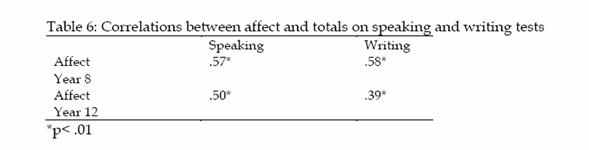

Table 6:

Correlations between affect and totals on speaking and writing tests

As can be

seen from Table 6, the computed correlations are higher for both

speaking

and writing scores in the Year 8 group. The difference is especially

prominent

in the case of writing.

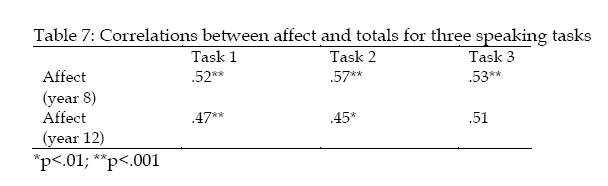

When

correlations were computed separately for the three oral tasks (Table 7),

a different

pattern emerged in the two groups. With Year 8 participants the coefficients

did not

range as widely as with Year

showed the

highest connection with picture description, while this was the just the

opposite

with the older group, where this presented the weakest relationship.

Year 12

participants showed the highest correlation between affect and argumentative

talk. In

each of the three oral tasks the coefficients were lower in Year 12

than in

Year 8.

Table 7:

Correlations between affect and totals for three speaking tasks

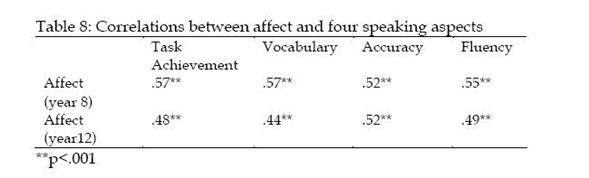

The

relationship of affect and the individual aspects of writing is, generally,

also

stronger in

Year 8 than in Year 12 (see Table 8). In Year 8, the strongest relationship

of affect

was found with task achievement and vocabulary use. In Year 12,

quite

interestingly, the strongest relationship was found with accuracy.

Table 8:

Correlations between affect and four speaking aspects

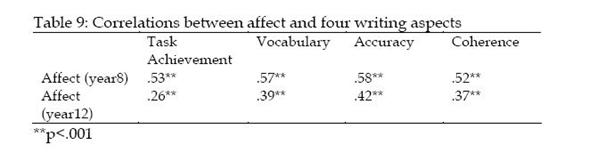

In the case

of writing aspects, coefficients were higher for Year 8 than for Year 12.

Affect in

younger participants was more strongly connected with accuracy and

successful

vocabulary use than with task achievement and text-composing skills.

With Year

12 participants the same pattern emerged, only – as already mentioned

– the

coefficients were lower in each case than those of Year 8 participants. These

coefficients

are presented in Table 9.

Table 9:

Correlations between affect and four writing aspects

Conclusions

On the

basis of the results we obtained it can be concluded that there is a

significant

relationship

between affect and productive skills of speaking and writing. It

is

particularly prominent in Year 8 learners. With Year 12 learners there seems to

be an

important difference in significance between the two skills: success in

speaking

seems to be more strongly related to affect than success in writing skills.

With

respect to the type of speaking activity it is interesting to note that with

older and

more proficient learners (Year 12) success in argumentative talk was

more highly

correlated with affect than the less complex activities of answering

questions

and picture description. Year 8 learners did not show differences in this

respect

and, overall, it seems that success in all types of speaking activities in

their

group was

connected with positive affect.

In terms of

the four assessed aspects of speaking Year 8 learners, again, did not

show much

difference in the strength of the relationship of affect and individual

aspects of

speaking skills. With older learners the differences seem prominent and

we can

conclude that affect was most highly correlated with accuracy, the aspect

that these

learners had the lowest success in. It is also interesting that with Year 12

learners

affect was less strongly related than with Year 8 learners to all speaking

skill

aspects except accuracy.

As has been

mentioned, success in writing was significantly less correlated

with affect

in the Year 12 group than with Year 8 learners. If we consider the four

criteria that

writing was assessed along, we can conclude that in both groups the

highest

correlation with affect was found where the scores were low: with accuracy.

Our

findings seem to point to two general conclusions about the relationship

between

affect and success in productive language skills. The first conclusion may

be

considered to be of developmental nature: the relationship is stronger for

younger and

less proficient learners. The second conclusion is connected to the

complexity

and difficulty of using productive skills: affect is more strongly connected

with more

complex activities.

If we

interpret the relationships evidenced by the significant correlation

coefficients

in terms of

affect as a cause of success, the teaching implications of these

findings are

quite apparent: we should help FL learners to create and maintain a

positive

affective profile.

Implications

for further study

In the

present study we used an instrument for measuring the general affective

profile of

participants. Perhaps more meaningful relationships could be obtained

if, along

with such an instrument, more state-like measures are taken as well. A

particular

task may be more or less motivating for a learner and trait and situation-

specific

items may not tap into state motivation, or state anxiety, that may

also

significantly influence learner behaviour and success on the task.

It might

also be a good idea to get information on how learners themselves assess

their

performance on tasks. Insights into which aspects of speaking and writing

performance

learners find more or less difficult may be very valuable for conclusions

about the

role and impact of affective factors in language learning.

Since our

younger learners (Year 8) had also learnt EFL for a shorter period of

time than

older ones (Year 12), it is possible that the developmental nature in our

first

conclusion in fact reflects the stage of language learning and not age. Which

of the two

possibilities is true could be found by studying participants of the same

age but at

different stages of learning.

References

Brumfit, C.

J. (1984). Communicative methodology in language teaching.

Burns, R.

(1982). Self-concept development and education.

Winston.

Bygate, M.

(2002). Speaking. In R. B. Kaplan (Ed.), The

linguistics

(pp. 27-38).

Clément, R.,

& Gardner, R. C. (2001). Second language mastery. In H. Giles & W.

P. Robinson

(Eds.), The new handbook of language and social psychology (2nd ed.,

pp.

489-504).

Common

European framework of reference. (2001).

Press.

Cumming, A.

(1989). Writing expertise and second language proficiency. Language

Learning, 39, 81-141.

Csizér, K.,

& Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The internal structure of language learning

motivation

and its

relationship with language choice and learning effort. Modern

Language

Journal, 89,

19-36.

Dörnyei, Z.

(1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom.

Modern

Language Journal, 78,

273-84.

Dörnyei, Z.

(2001). Teaching and researching motivation.

Dörnyei, Z.

(2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in

second

language acquisition.

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dörnyei, Z.,

& Otto,

Working

Papers in Applied Linguistics 4, 43-69.

Gardner, R.

C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of

attitudes

and

motivation.

Horwitz,

E.K. (2000). It ain’t over ‘til it’s over: On foreign language anxiety, first

language

deficits, and the confounding of variables. Modern Language Journal,

84, 256-259.

Horwitz, E.

K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom

anxiety. Modern

Language Journal, 70, 125–32.

Julkunen,

K. (1989). Situation- and task-specific motivation in foreign language

learning

and

teaching. Joensuu:

Laine, E.

J. (1987). Affective factors in foreign language learning and teaching: a

study of

the ”filter.”

Levelt, W.

J. M. (1983). Monitoring and self-repair in speech. Cognition,14,

41-104.

Littlewood,

W. T. (1981). Communicative language teaching: An introduction.

MacIntyre,

P.D. (1995). How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply

to

MacIntyre,

P.D. (1995). On seeing the forest and the trees: a rejoinder to Sparks

and

Ganschow. Modern Language Journal, 79, 245-248.

22 UPRT

2006: Empirical studies in English applied linguistics

MacIntyre,

P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on

cognitive

processing in the second language. Language Learning, 44,

283-305.

Mihaljević

Djigunović, J. (1998). Uloga

afektivnih faktora u učenju stranoga jezika.

Filozofski

fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu.

Nikolov, M.

(2002). Issues in English language education.

Raimes, A.

(1985). What unskilled ESL students do as they write?: A classroom

study of

composing. TESOL Quarterly, 19(2), 229-258.

Rivers, W.

(1968). Teaching foreign language skills.

Press.

Silva, T.

(1993). Toward an understanding of the distinct nature of L2 writing. TESOL

Quarterly,

27 (4), 657-677.

Scovel, T.

(1991). The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the

anxiety

research. In E. K. Horwitz & D. J. Young (Eds.), Language anxiety.

From

theory and research to classroom implications (pp.15-23).

NJ:

Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Sinclair,

J. McH. (1987). Classroom discourse: Progress and prospects. RELC Journal,

18, 1-14.

Skehan, P.

(1998). Task-based instruction. In W. Grabe et al. (Eds.), Annual review of

applied

linguistics 18: Foundations of second language teaching (pp. 268-286).

Sparks, R.

L., & Ganschow, L. (1991). Foreign language learning difficulties:

Affective

or native

language aptitude differences? Modern Language Journal, 75,

3-16.

Sparks, R.,

& Ganschow, L. (1993). Searching for the cognitive locus of foreign

language

learning

difficulties: Linking first and second language learning. Modern

Language

Journal, 77,

289–302.

Sparks, R.

L. & Ganschow, L. (1995). A strong inference approach to causal factors

in foreign

language learning: A response to MacIntyre. Modern Language

Journal,

79, 235-244.

Sparks, R.

L., Ganschow, L., & Javorsky, J. (1995). I know one when I see one (Or, I

know one

because I am one): A response to Mabbot. Foreign Language Annals,

28, 479-487.

Sparks, R.

L., Ganschow, L., & Javorsky, J. (2000). Déjà vu all over again: A response

to Saito,

Horwitz, and Garza. Modern Language Journal, 84, 251-255.

Ushioda, E.

(1996). Learner autonomy 5: The role of motivation.

Ushioda, E.

(2003). Motivation as a socially mediated process. In D. Little, J.

Ridley,

& E. Ushioda (Eds.), Learner autonomy in the foreign language classroom:

Teacher,

learner, curriculum, assessment (pp. 90-102).

Widdowson,

H. G. (1998). Skills, abilities, and contexts of reality. In W. Grabe et al.

(Eds.), Annual

review of applied linguistics 18: Foundations of second language

teaching

(pp. 323-333).

Wittrock,

M. C. (1986). Students’ thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook

on

research on teaching (pp.

297-313).

Zamel, V.

(1983). The composing processes of advanced ESL students: Six case

studies. TESOL

Quarterly, 17 (2), 165-186.

Appendix

Items in

the Affective profile questionnaire:

1. I like

English very much.

2.

Knowledge of English is useless to me.

3. My

parents think that it is important for me to know English.

4. People

who speak English are interesting to me.

5. I’m

interested in films and pop music in English.

6. I find

English lessons extremely boring.

7. I have

no feeling for languages, I’m a hopeless case for learning languages.

8. I find

it easy to learn English.

9. It would

take much more effort and will for me to be more successful at English.

10. No

matter how much I study I can’t achieve better results.

11. I like

to use English in my free time.

12. I often

fail while learning English.

13. I feel

anxious when speaking English during English lessons.

© University

of Pécs Roundtable 2006: Empirical Studies in English Applied Linguistics

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 2.- CLASSROOM BLOGGING: TWO FUNDAMENTAL

APPROACHES

2.- CLASSROOM BLOGGING: TWO FUNDAMENTAL

APPROACHES

Our

dear SHARER Marcela Francese has sent us this article to SHARE:

Classroom

Blogging: two fundamental approaches

By Aaron Campbell

·

October 10, 2005

I kicked off my

visit to the JALT 2005 conference yesterday in

One of the most

poignant issues for me that arose in the discussion involved motivation and

evaluation. We spoke about two fundamental approaches to classroom blogging.

The first approach to getting students to blog is through extrinsic factors of

quantitative evaluation and accountability. Students are given blogging

assignments at consistent intervals, and the teacher tracks the quantity of student

posts and comments, considers the quality of writing and effort, and finally

assigns points or grades accordingly. This ‘crack the whip’ method coerces

students to post to their blogs, read other posts, and comment on them. In

doing so, students will read, write, and post; and if they don’t, they either

receive a lower grade or, depending on the assigned value of blogging in the

curriculum, fail altogether. In the end, students will have most likely

improved their reading and writing skills, gotten some insightful feedback from

others to consider, and have even exercised their reflective and critical

skills. Whether or not students will enjoy blogging, see the potential value of

it, and continue blogging on their own after the course is finished is secondary

to the pedagogical goals set by the teacher.

The second

approach involves drawing upon the factors of motivation intrinsic to each

student. In this case, the teacher takes a qualitative approach to getting

students to blog, encouraging them to write about their interests, use social

networking tools to meet new people, post photos and sound files, etc. An

important aspect of this approach is to see the act of blogging as something

fun, expressive, enjoyable, conversational, and poetic. The blog can and should

be anything the student wants it to be. The teacher sees herself as a

facilitator of a process of creation, not as an enforcer of behavior. She makes

no demands on quantity and does everything she can to inspire her students to

blog through her own examples, stories, enthusiasm, and passion. Qualitative

and reflective self and peer evaluation are both encouraged and valued; and

students are given considerable, if not complete, control over the pace,

content, and direction of their blogging activities. Whether or not students

will enjoy blogging, see the potential value of it, and continue blogging on

their own after the course is finished is the primary consideration.

I am certain that

few teachers adhere to either one of these two approaches exclusively; most,

rather, are striving to find some sort of middle ground that works for their

particular situations. In my own practice, for example, although I resonate

with the qualitative approach philosophically, I can see that certain elements

of the ‘crack the whip’ approach, like structured homework assignments, are

necessary to induce my learners into the blogging process, positioning them in

such a way that makes the second approach possible. After twelve years of being

exposed to authoritative methods of heavy testing, rote memorization, and

deference to superiors, it is virtually impossible for most of my students to

view the act of blogging as being anything other than part of the only kind of

schooling they have ever come to know. Breaking down this mental barrier is the

first obstacle to overcome if a blog-driven movement toward more autonomous

language learning is to be achieved.

Until now, my

approach has been to design assignments that mimic the activity of a

self-directed blogger: choosing a topic to write about, using social networking

tools and tags to find other bloggers, linking to those bloggers in the posts,

linking to resources for further reading, connecting ideas and expressions of

emotions to images and photos, following up on comments in future posts, etc.

My hope is that by acting like bloggers, they can get a taste for what it feels

like to communicate their own ideas in a foreign language and develop their own

social network based on their interests. They will also be in possession of a

tool that empowers them to be in control of this process and encourages them to

interact in a direct way with their peers. If they can come to this

understanding of blogging through the weekly assignments and reflective

evaluations, then they are in a position to decide whether or not to continue

engaging in the medium after the term is finished. The beauty of using blogs

this way is that students own the tools, the content they create, and their

online identity and social network of which they are a part. Ideally, their

blogs won’t reek of institutional affiliation and all the emotional baggage

that comes with it, making it far more likely that learners will come to

embrace them as both learning tools and vehicles for expression and discovery.

© 2005 by Dekita.org

Open EFL/ESL

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 3.- ADVANCED

VOCABULARY IN CONTEXT: WHAT WE WEAR DOWN-UNDER!

3.- ADVANCED

VOCABULARY IN CONTEXT: WHAT WE WEAR DOWN-UNDER!

What We Wear Down-Under!

By Mark Gwynn

As a kid

growing up on the beaches of

The

evolution of the swimming costume from neck-to-knee to dps reflects a history of cultural

attitudes to the body and to the beach in

In the

The Women

are donning shirts

And the men

in the seaside places

Have taken

to wearing skirts.

Sing hey,

for the whiskered women

In trailing

skirts encased

Sing ho,

for the dainty fellows

And clasp

them round the waist.

After a

large protest in

When

Australians did venture into the surf in these early years they had a number of

Standard English words to describe what they wore. Words including costume, attire, gown, trunks, and suit were used in England and were often

qualified by 'swimming' or 'bathing'--hence swimming costume, bathing attire, bathing costume, etc. The

A growing

interest in swimming in the early years of the twentieth century brought to

public attention the issue of acceptable and non-acceptable swimming costumes

in

We are

essentially a clothes-wearing people. ... It is immodest for ladies to appear

on open beaches amongst men in attire so scant that they would be ashamed to

wear the same dress in their own drawing-rooms (as quoted in H. Gordon, Australia

and the Olympic Games, 1994, p. 80).

The

notoriety and publicity surrounding these celebrities and the influence of

fashion led to calls in

The

multi-piece and two-piece costumes became less fashionable and by the 1920s

David Jones was advertising the 'Orient One-piece Canadian Costume from ten

shillings and six pence'. But while the less cumbersome one-piece swimming

costume became more popular, there were many who believed that it was too

revealing. A common practice of men before and after the First World War was to

wear Vs over the

costume. These were like an athlete or circus performer's trunks and, although

worn ostensibly for decency, they only served to accentuate the male anatomy.

The demand for a swimming costume that was prescribed by the authorities and

that could stem the tide of experimentation laid the foundations for the neck-to-knee

costume.

The first

Australian word used for a swimming costume, neck-to-knee, indicates the competition between

the forces of imported English culture and the newly emerging Australian

culture. The Australian National Dictionary (AND) has evidence of neck-to-knee

from 1910, although it

cites a

All people

bathing in any waters exposed to view from any wharf, street, public place, or

dwelling-house in the Municipal District of Manly, before the hour of

Even with

these restrictions an increasing number of Australians were going to the beach

in the years leading up the First World War. In 1906 the first Surf Life Saving

Club opened--in Bondi--with many others soon following. The increase in the

number of Australians visiting the beach meant that the legal prescriptions

regarding swimming were often challenged and in a sense the word neck-to-knee

is not simply

descriptive but intimates the restrictions that enforced its use. Many

photographs and drawings of people at the beach in the early years of the

twentieth century show that the prescribed neck-to-knee was competing with other more

revealing costumes. It is in this period when the prescribed dress codes were

being challenged that we find the first evidence of the Australian words togs, swimmers, bathers, and cossies .

The word togs is an abbreviation of the

sixteenth-century criminal slang togeman, meaning 'coat'. Togeman itself comes from the Roman 'toga',

which comes from the Latin tegere 'to cover'. The first citation for togs in the OED dates from 1708, when it

was still considered a part of the flash language of the criminal underworld.

Later in the eighteenth century togs was used as slang or humorously for clothes--the OED has a 1779 citation

for this sense. So by the time the First Fleet left

The next

evidence the AND has of an Australian word for swimming costume is the simple

abbreviation cossie, first

recorded in 1926. The evidence for cossie points to the still common use of 'swimming

costume' and 'costume' in Australian English between the wars. Cossie is a less cumbersome and less formal

way of denoting an item of clothing used primarily for pleasure. Other early

examples of Australian words for swimming costume show this tendency of

shortening a word or modifying the meaning of an existing word. The OED marks swimmers as a chiefly Australian word,

although the first evidence for it comes from an English newspaper in 1929. Our

first evidence for bathers comes from Katharine Susannah Prichard's Haxby's Circus (1930).

In the eighteenth century, bather was used to describe someone who had a bath. By

adapting these existing nouns used to describe a person who swims or bathes to

the clothes worn while swimming or bathing, the Australian vocabulary was able

to keep pace with new cultural attitudes to swimming and, importantly, to the

fashion emerging on the beach.

In 1928 the

MacRae Knitting Mills in

Many of the

early terms for swimming costume in Australia were the same for both sexes

(what they wore often amounted to the same thing) but with changing fashions

and the popularity of the men's trunk-style costume, the terms were applied

largely to them. Partly because the speedo style of costume proved practical and

comfortable in the surf and in the swimming pool, they soon became the most

popular swimming costume for Australian men and boys. Many boys grew up calling

this particular swimming costume their speedos, cossies, bathers, togs, or swimmers . All these Australian words are

descriptive--they describe something in terms of an article of clothing or

through association with bathing and swimming. They are all words specific to

the object they describe. The next generation of Australian words for speedos highlights what the object

covers--the male genitals. Because many of the following words are or were

considered vulgar, or colloquial at best, the earliest evidence we have at the

Australian National Dictionary Centre is not a clear indication of when these

words were first used. Many of them probably emerged in the decades following

the end of the Second World War, most likely in the 1960s and 1970s, when

challenges to sexual taboos were controversially played out in the public

domain. This is the period when bikinis and even topless women were seen

regularly on the beaches of

The

earliest evidence at the ANDC of a term emphasising what is covered by the

costume (i.e. the genitals) is the word sluggos, from a 1972 edition of the Australian

surfing magazine Tracks . The word is probably formed from 'slug'

meaning 'penis' (originally from Australian Navy slang), and from the last

syllable of speedos . Another

possibility is that the word refers to the appearance of having a slug in your speedos . We have evidence that this word is

still in use today, although the citations have moved away from the surfing

context, and there is growing evidence for sluggers . While I can remember, and still

use, the word dps ('dick pointers') from the late 1970s, there is currently only evidence

of it from the Internet in the last couple of years and from previous responses

to Ozwords --but there are certainly quite a few people in Wollongong

who still use it! Our first evidence of dick-stickers is similarly late, coming from a

1993 edition of the Sydney Morning Herald : 'At

The Inuit

people have had practical reasons for developing an extensive vocabulary to

describe snow and ice features. In Australian English the numerous terms for

the men's speedo costume

are more a result of fashion and sex. The early terms, including togs and cossies, reflect the growing popularity and

emerging culture of the beach and swimming. The growth of later terms,

including dps and budgie

smugglers, shows a

common characteristic of English words associated with sex in that they

generate many synonyms. The diversity of these terms is also reflected in their

apparent regionalism. Togs is more likely to be heard in

About the

Author

Mark Gwynn

is a researcher at the Australian National Dictionary Centre.

© 2003 by The

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 4.- 10th LATIN AMERICAN ESP COLLOQUIUM

4.- 10th LATIN AMERICAN ESP COLLOQUIUM

August

9th , 10th & 11th - 2007

Venue:

Departamento de Lenguas - Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto

Ruta

No

The Latin

American ESP Colloquia provide a forum for sharing teaching and research

experiences in the fields of ESP and EAP at tertiary and university levels.

This academic event started in

The 10th Latin

American ESP Colloquium will provide a forum for sharing research results or

experiences of research projects that are being carried out in the fields of

ESP and EAP at university level.

Abstracts and papers should include a description of the topic for the

colloquium and the same name and affiliation of each of the invited

participants. All colloquia will be open only to presenters.

The 10th ESP Colloquium invites research proposals on topics related to:

·

ESP

and EAP

·

Discourse

·

Genre

·

Text

Analysis

·

Course

Design

·

Materials

Design

·

Needs

Analysis

·

Evaluation

·

Assessment

and Testing

·

Teacher

Training

·

Schema

Theory

·

Distance

Education

·

Educational

and research technology

Proposals which

address theory, research and applications as well as describe innovative

projects are encouraged.

Deadlines & Important Dates

Abstract

Submissions: March 30th, 2007

Submission of

complete papers: April 30th, 2007

Authors

Notified: May 30th, 2007.

Early

Registration: June 10th, 2007

Advance

Registration: July 10th, 2007

Registration Fees

Early

Registration: U$S 100 (by June 10th, 2007)

Advance

Registration: U$S 150 (by July 30th, 2007)

The registration Fees include entry to: Invited speakers, Paper, Panel and Discussions; Refreshment breaks; Abstract Book; and CD-ROM Proceedings.

For further

information, please contact the 10th Latin American ESP Colloquium organizers

at espcolloquium@hum.unrc.edu.ar

-----------------------------------------------------------

![]() 5.-

OCTAVAS JORNADAS NACIONALES DE LITERATURA COMPARADA

5.-

OCTAVAS JORNADAS NACIONALES DE LITERATURA COMPARADA

Octavas Jornadas

Nacionales de Literatura Comparada

Facultad de Filosofía y

Letras - Universidad Nacional de Cuyo

Mendoza,

Han sido invitados, entre

otros académicos comparatistas, Dr. Jean Bessière (París), Dr. Manfred Beller

(Bergamo), Dr. Hugo Dyserinck (Aquisgrán) Dr. Anil Batí (Bombay), Dr. Axel

Gasquet (Clermont Ferrand), Lic.María Kodama (Fundación Internacional

J.L.Borges).

Áreas temáticas.

1. Exclusiones.

Hibridación. Mestizaje. Tematología transnacional e intercultural.

2. Interculturalidad. Fronteras de interdisciplinariedad: Literatura y otras

Artes, Literatura y Ciencias, Literatura e Historia, Literatura y Filosofía.

Literatura y Cine, Literatura y Política, Literatura y ciber espacio.

3. Intermediación, sus

agentes: viajeros, traductores, críticos, prácticas docentes, prácticas

editoriales. El escritor como mediador cultural.

4. El texto como espacio

de encuentros. Historia literaria comparada. Nuevas redes transnacionales /

transculturales.

5. La lengua y los

fenómenos transculturales. Francofonía, anglofonía, hispanofonía, lusofonía.

6. Recepción y

transferencia. Traducir, apropiarse, transplantar esquemas conceptuales y

prácticas comparatistas. Teoría literaria comparada. Texto y contexto.

7. Traducción cultural:

tender puentes entre lo propio y lo otro. Globalización. “comparatisme

planetaire”, “remapping knowledge”. Migraciones, Literatura de minorías.

Literatura de fronteras. Género y Literatura.

Como es habitual en las

Jornadas de

Comisión Directiva:

Presidente: Lila Bujaldón

de Esteves (UNCuyo)

Vicepresidente: Adriana

Crolla (Universidad Nacional del Litoral)

Secretaria: Elena

Duplancic de Elgueta (UNCuyo)

Tesorera: Claudia Garnica

de Bertona (UNCuyo).

Aranceles:

Expositores socios de

Expositores no socios de

Expositores estudiantes:

deberán contar con el aval de un profesor de la institución a la que

pertenecen. Inscripción anticipada: $25. Con posterioridad: $35.

Estudiantes asistentes

con certificado $15

Estudiantes (oyentes) y

asistentes sin certificado: sin cargo.

Dirección electrónica: literaturacomparada@yahoo.com.ar

Dirección postal:

Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Gabinete 305. Centro Universitario. Parque

General San Martín, cc.345, C.P. 5500 Mendoza

------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 6.-

I CONGRESS OF THE BRAZILIAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY

TEACHERS

6.-

I CONGRESS OF THE BRAZILIAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY

TEACHERS

OF ENGLISH

Our dear

SHARER Vera Menezes de Oliveira e Paiva has sent us this information tpo SHARE:

Congresso

Internacional da ABRAPUI - "New Challenges in Language and

Literature"

Faculdade

de Letras da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte

3rd to 6th June

2007

Conference

organization:

ABRAPUI - Brazilian Association of University

Teachers of English

Vera Lúcia

Menezes de Oliveira e Paiva,

Chair,

Organizing Committee

Gláucia

Renate Gonçalves,

President,

ABRAPUI

Introduction

ABRAPUI is

an academic and cultural association whose aims are the organization of

academic conferences, the dissemination of literary and critical/theoretical

works, and cultural exchange.

During

ABRAPUI’s business meeting, its members decide on a theme for the next

conference, and the members of the English Language and Literatures in English

scientific committees are responsible for the academic program of the

conference.

ABRAPUI’s

conferences began in 1970, and were alternately dedicated to English Language

and Literatures in English. In 2003 and 2005 the language and literature

conferences were simultaneous. Given the success of this initiative, as well as

the international nature of the meetings, we are now pleased to announce the

1st International ABRAPUI Conference, to be held at the College of Letters at

the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Belo Horizonte, MG), June 3 to 6, 2007.

Confirmed

speakers:

Ana Lúcia

Gazzola - UFMG

Connie Eble

-

Tim Murphey

-

David Block

-

Helena

María Viramontes -

Sylvia

Adamson -

Smaro

Kamboureli -

Sérgio Bellei -UFSC

Sônia Torres -UFF

Solange

Ribeiro de Oliveira -UFMG

Lynn Mario de

Souza -USP

Walkyria Montmor -USP

Laura Miccoli -UFMG

Stella

Tagnin- USP

Program

The final

program will be posted after the registration deadline for presentations (March

31, 2007)

Researchers

from

Preliminary

Program:

June 3

18:30

Registration

19:00

Opening Lecture: Language and Literature in a Changing World - Ana Lúcia

Gazzola

20:30 Cocktail

June 4

08:30 -

09:45 Lectures:

Identity in

Second Language Learning Research: Where We Have Been and Where We Are at

Present - David Block

Between

Disciplines and Methods: Asian Canadian Literature and CanLit - Smaro

Kamboureli

Break

Coffee Break

10:00 -

11:00 Paper Sessions

11:00 – 12:00

Paper Sessions

Lunch

14:00 -

15:30

Round

Tables:

1.

Identities in Language and Literature

2.

Indigenous Identities and Diversity in the Contemporary Literature of the

3. New

Challenges in the Classroom

15:30 –

16:45 Symposia

Break Coffee

Break and Poster Exhibit

17:15 –

18:30 Lectures:

Classroom

English-Teaching/Learning in

Laura

Miccoli

Representing

Multitudes: Struggling with Old and New Histories - Sonia Torres

18:30 – 19:00

Book Signing and Special Performance

ABRAPUI

Business Meeting

June 5

08:30 –

09:45 Lectures:

Intermediality

or Interart Studies? - Solange R. de Oliveira

New

challenges in Language Teaching (As Novas Orientações Curriculares para o

Ensino Médio: Língua Inglesa) -Lynn Mario T. Menezes de Souza e Walkyria

MonteMór

Break

Coffee Break

10:00 –

11:00 Paper Sessions

11:00 –

12:00 Paper Sessions

Lunch

14:00 -

15:30

Round

Tables:

1. New

Challenges in Gender Studies and Feminist Criticism

2. New

Challenges in Distance Education

3. New

Challenges for the Study of Emily Dickinson

4. Genre as

a Challenge for Language Teaching

15:30 –

16:45 Symposia

Break

Coffee Break and Poster Exhibit

17:15 –

18:30 Lectures:

Slang and

the Internet - Connie Eble

Marks of a

Chicana Corpus: An Intervention in the Universality Debate - Helena María

Viramontes

18:30 Break

19:00

Optional Dinner

June 6

08:30 –

09:45 Lectures:

Towards a

New Historical Stylistics - Sylvia Adamson

Learning

Ecologies of Linguistic Contagion - Tim Murphey

Break

Coffee Break

10:00 –

11:00 Paper Sessions

11:00 – 12:00 Paper Sessions

Lunch

14:00 –

15:30

Round

Tables:

1. New

challenges in Teacher Education

2.

Transnational Movements in Literature and Film

15:30 –

16:45 Symposia

Break

Coffee Break and Poster Exhibit

17:15 –

18:30 Lectures:

Hypertext,

Information Overload, and (the Death of) Literature - Sérgio Bellei

Corpora

Studies as a New Challenge for Language Professionals - Stella E. O. Tagnin

18:30

Closing Session

Contact:

ABRAPUI /

FALE / UFMG

Address: Av. Antônio Carlos 6627 – sala 4015 - 31270-901 Belo Horizonte – MG

Phone

number: (0xx31) 3499-5133

E-mail: abrapui@abrapui.org

Website: www.abrapui.org

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 7.- SEMINARIOS DE

7.- SEMINARIOS DE

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL

Universidad Nacional de

Rosario

Maestría en Literatura

para Niños

Dirección:Dr. Ovide

Menin

Secretaría Técnica:

Mgter. María Luisa Miretti

Seminarios 2007

Horarios:

Jueves

Abril (fechas

por confirmar)

Dr.

Ovide Menin

Seminario:

Psicología del Niño

Mayo 17,

18 Y 19

Dra.

Cristina Bloj

Seminario:

Psicoanálisis

Junio (fechas

por confirmar)

Dr. Félix Temporetti

Seminario:

Taller II: Teorías del Aprendizaje y Prácticas Docentes con Niños.

Agosto 9,

10 y 11

Dr.

Alejandro Raiter

Seminario:

Sociolingüística

Octubre

(fechas por confirmar)

Mgter.

Beatriz Actis

Seminario:

Taller III Relaciones de

Noviembre

(fechas por confirmar)

Prof.

Fernando Avendaño

Seminario:

Psicolingüística

Información: mlmiretti@gigared.com

0341- 4802676 interno

129

------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 8.- FIRST CONGRESS FOR TEACHERS OF ENGLISH

IN CONCEPCIÓN

8.- FIRST CONGRESS FOR TEACHERS OF ENGLISH

IN CONCEPCIÓN

Our dear

SHARER Lucia Perrone from Career Opportunities has got an announcement to make:

“Resources for Teachers”

I Congress for Teachers of English - Organised by Career Strategies

April 26, 27 and 28, 2007

Colegio Nacional Justo

José de Urquiza, Concepción del Uruguay, Entre Ríos, Argentina

Speakers and Workshops

Ana María

Rozzi de Bergel

Effective activities for error exploitation: teaching, rather than correcting

Charlie López

Listening Ideas!

Chris Kunz

Sorting out the massive amount of everyday Englishness II

Laura Renart

Teaching the Bilingual Child

What is new about old reading and writing?

What's at hand? Preparing your class with ...what you have

María Belén G. Milbrandt

Gladiators´School: Helping Polonius kill the lion! (Teaching Business English)

María Marta Suárez

Story Telling: from the cradle to kindergarten and beyond

Look, Move, Sing and Say in Kindergarten

Marta Schettini

Reading with our five senses.

To take into account

Handouts with ready-to-be-used activities included

Free access to “Aguas Claras” hot spring waters.

Raffles

Commercial Presentations

Pizza time on Friday night included

Enrolment Deadline: April 21

Registration Fee

Until March 31 - $100

Until April 21 - $110

Methods of Payment: Bank Deposit or Bank

Transfer to: Banco de

Banco Francés- Sucursal

212 - Caja de Ahorro: No. 312921/1 - CBU 0170212740000031292111

To confirm your enrolment, please send a copy of your proof of payment at career-strategies@hotmail.com

For further information and enrolment, contact: career-strategies@hotmail.com

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 9.- III SIMPOSIO

NACIONAL “ECOS DE

9.- III SIMPOSIO

NACIONAL “ECOS DE

LUGAR: Facultad de

Filosofía y Letras – Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza.

Para informes e

inscripción dirigirse a Secretaría de Extensión Universitaria de

Página WEB: http://ffyl.uncu.edu.ar ®Secretaría de Extensión

III Simposio Nacional

“Ecos de

III Simposio Nacional

“Ecos de

Para informes e

inscripción dirigirse a Secretaría de Extensión Universitaria de

Página Web: http://ffyl.uncu.edu.ar ®Secretaría de Extensión

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 10.- INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR DIALOGUE ANALYSIS: III

COLOQUIO ARGENTINO

10.- INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR DIALOGUE ANALYSIS: III

COLOQUIO ARGENTINO

Our dear

SHARER Leticia Móccero has sent us this information:

III Coloquio Argentino de

Facultad de Humanidades y

Ciencias de

Grupo Eclar (El Español

de Chile y Argentina)

Sede

Jockey Club Multiespacios

- Av. 7 Nº 834 -

Tema: Diálogo y Contexto

Por tercera en vez en

nuestra ciudad realizaremos un encuentro académico para abordar temáticas

vinculadas con la lengua hablada. Considerar el diálogo en contexto significa

incursionar en el ámbito de la oralidad situada, tanto en medios

institucionales como privados. Convocamos a quienes trabajen en este ámbito a

presentar trabajos que aborden aspectos del tema desde diferentes prespectivas

de análisis y que muestren resultados de trabajos empíricos, de investigaciones

concluidas o en curso, revisiones críticas de marcos de análisis o métodos de

investigación.

Idiomas oficiales:

Español e Inglés

Presentación de resúmenes

y plazos

1. Forma de presentación

Quienes estén interesados

en hacer una presentación en el coloquio deberán enviar un resumen de su

trabajo.

Características del

resumen

Procesador: Word for

Windows 6.0, 2000 o inferior.

Extensión: entre 200 y

250 palabras aproximadamente.

Tipo de letra: Times New

Roman, tamaño 12.

Interlineado: sencillo

Incluir la siguiente

información:

Forma de Presentación:

Poster, Ponencia Independiente o Ponencia Coordinada.

(Alineación derecha, con

mayúscula). Luego, separados por un espacio,

Título del trabajo: (en

negrita) alineación izquierda.

Autor o autores:

(Apellido, en mayúsculas y nombres, en minúsculas) Alineación derecha.

Institución a la que

pertenecen: (en minúsculas). Alineación derecha.

E-mail: Alineación

derecha y debajo de cada nombre.

(Las palabras

"título", "autor", "institución",

"e-mail" NO deberán incluirse).

Ejemplo:

Luego se incluirá el

resumen del trabajo, justificado, sin indentación y separado de la dirección

electrónica por un espacio. El texto se escribirá en un solo párrafo. (NO escribir

la palabra "resumen")

Envío: Por correo

electrónico en archivo adjunto

Asunto: Resumen IADA

Dirección electrónica: info@iada-agentina.com.ar

Se enviará confirmación

automática de recepción.

2. Fechas importantes:

Fechas límite de

recepción:

Propuestas para ponencias

coordinadas: hasta el 15 de diciembre de 2006

Ponencias coordinadas:

hasta el 10 de abril de 2007

Ponencias

independientes:hasta el 20 de abril de 2007

Aviso de aceptación de

los resúmenes:

Por correo electrónico

dentro de los cinco días a partir de la recepción del resumen. (Si en ese lapso

no reciben comunicación alguna, les solicitamos que vuelvan a contactarse con

Inscripción y aranceles

Importante : Las fichas

de inscripción, tanto de los expositores como de los asistentes, se recibirán

hasta el 30 de abril de 2007, fecha en que se enviará a la imprenta el material

gráfico. No podremos garantizar la entrega de dicho material a quienes no cumplan

con este plazo.

Para completar el trámite

de inscripción al Coloquio es necesario rellenar el formulario que figura en el

link "ficha de inscripción", consignando todos los datos que se

solicitan. El pago de los aranceles deberá efectuarse mediante giro postal, a

nombre de María Leticia Móccero, o personalmente en el momento de la

acreditación. No podemos aceptar cheques personales ni pago mediante tarjetas

de crédito.

Importante: No enviar

giros durante el mes de enero

Categoría de

participante:

Expositor: Organizadores

de sesiones de Ponencias Coordinadas, Participantes que presentan Ponencias

Coordinadas, Ponencias Independientes o

Posters.

Asistentes: Participantes

que no presentan trabajo.

Alumnos de grado (Con

comprobante): El arancel corresponde al costo de los materiales que se

entregarán durante el coloquio.

A partir del 1 de Marzo

de 2007

Expositores $ 140

Asistentes $ 90

Alumnos $ 10

Nota: Todos los

asistentes al Coloquio que sean co-autores de un trabajo deberán inscribirse

como "expositores", aunque la presentación sea hecha por un solo

integrante del equipo.

Para la presentación de

trabajos en el coloquio será necesaria la presencia de por lo menos uno de sus

autores.

Dirección postal para

envío de correspondencia y giros postales:

María Leticia Móccero.

Calle 29 Nº 1769 - (1900)

Ponencias

Coordinadas. Temas 15/03/2007

Nº 1

Tema: El Género en

Coordinadoras

Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de

Esta

Enviar resúmenes a: lgranato@isis.unlp.edu.ar

(o a la dirección del Coloquio)

Nº 2

Tema: Discurso Académico y Oralidad

Coordinadora: Dra. María Marta García Negroni.

UBA y CONICET

El tema general de este panel de “ponencias coordinadas” es “Discurso académico

y oralidad” y su propósito es presentar los resultados de investigaciones

concluidas o en curso sobre la cuestión. En el panel, podrán incluirse los

trabajos que, desde distintas perspectivas, aborden aspectos

lingüístico-discursivos específicos de los diferentes subgéneros del discurso

académico oral en español o que contribuyan a marcar las relaciones,

dependencias y diferencias entre oralidad y escritura en el ámbito del discurso

académico en nuestra lengua.

Enviar resúmenes a: mmgn@fibertel.com.ar

o a la dirección del Coloquio

Nº 3

Tema: Fonética y Fonología en

Coordinadoras: Dra. María Amalia García Jurado y Dra. Claudia Borzi

Este panel de “ponencias coordinadas” agrupará estudios, sobre el español u

otras lenguas, dedicados a fenómenos fonéticos y fonológicos que estén

relacionados con aspectos de orden gramatical y discursivo. Interesan tanto la

presentación de los resultados de investigaciones terminadas como los

resultados parciales de investigaciones en desarrollo. El objetivo es abrir un

espacio de intercambio y discusión sobre la influencia de las particularidades

del habla en la constitución de la gramática y del discurso.

Enviar resúmenes a: majurado@filo.uba.ar

, cborzi@filo.uba.ar o a la dirección del Coloquio

Nº 4

Tema: Diálogos en clase de lengua extranjera

Coordinadora: Mgtr. Estela Klett

El panel de ponencias coordinadas “Diálogos en clase de lengua extranjera” reunirá

estudios sobre interacciones en el aula de idiomas. Se tratará del análisis de

alguno de los intercambios que allí tienen lugar: entre el docente y el

grupo-clase, entre aprendientes, o bien, aquellos presentes en textos de

enseñanza (consignas, diálogos, juegos de roles, entre otros). Podrán incluirse

trabajos que aborden el tema desde una perspectiva fonética, lingüística,

discursiva o pragmática. La finalidad del debate es describir la especificidad

del discurso didáctico en la clase de lengua extranjera a partir de diferentes

marcos de análisis.

Enviar resúmenes a: eklett@filo.uba.ar o

a la dirección del Coloquio

Nº 5.

Tema:Diálogo(s) Multicultural(es)

Coordinadora: Dra. Angelita Martínez

Este panel de ponencias coordinadas recogerá trabajos vinculados al contacto

lingüístico que den cuenta del fenómeno a través del análisis de producciones

orales de diversa naturaleza (análisis de conversaciones, relatos, entrevistas,

entre otros materiales). Los trabajos presentados pueden ser el resultado de

investigaciones en curso o finalizadas, a partir de las cuales se espera

conformar un espacio de reflexión sobre el aporte del campo a la lingüística

teórica y a sus aplicaciones.

Enviar resúmenes a: angema@filo.uba.ar o

a la dirección del Coloquio

Para mayor

información acerca de las actividades

programadas, se ruega consultar nuestra página web: http://www.iada-argentina.com.ar

Dirección de contacto: info@iada-argentina.com.ar

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() 11.- WORKSHOP ON

HOW TO TEACH ENGLISH IN KINDERGARTEN

11.- WORKSHOP ON

HOW TO TEACH ENGLISH IN KINDERGARTEN

Our dear SHARER Ana Kuckiewicz has sent us this invitation: